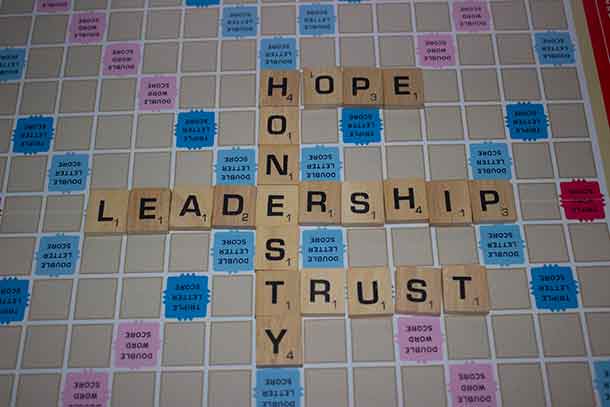

The new leadership is a blend of personal and interpersonal skills that form the basis of your ability to impact, influence and inspire others

By Carol Kinsey Goman

Columnist

BERKELEY, Calif. – BUSINESS – Most executives agree that collaboration is more important than ever in today’s turbulent business environment.

A company’s very survival may depend on how well it can combine the potential of its people and the quality of the information they possess with their ability – and willingness – to share that knowledge throughout the organization.

Deloitte’s recent Future of Work research found 65 per cent of the chief executives surveyed have a strategic objective to transform their organization’s culture with a focus on connectivity, communication and collaboration.

But collaboration doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It takes strategic leadership. Whether you’re an executive, team leader or first-line supervisor in an organization looking to build a more collaborative culture, the requirements for your job have changed.

In contrast to control-minded leaders of the past, today’s most effective leaders exercise a different kind of power. As one Silicon Valley CEO told me, “There is absolutely nothing wrong with command and control. It’s simply irrelevant in the 21st century.” The new leadership is a blend of personal and interpersonal skills that form the basis of your ability to impact, influence and inspire others.

To help you optimize the power of collaboration, here are six crucial leadership behaviours:

Silo busting

The collaboration that’s so critical for engagement, innovation and financial success is being blocked by knowledge-hoarding silos.

Silo is a business term that has been passed around and discussed in boardrooms over the last 30 years. Unlike many other trendy management buzzwords, this is one issue that hasn’t disappeared. Silos are viewed as a growing pain for organizations of all sizes.

Silo mentality describes the mindset present when departments, divisions or sectors don’t share information with others in the same company. Wherever it’s found, this mentality becomes synonymous with power struggles, lack of co-operation and loss of productivity.

Silo mentality can cause organizations to misallocate resources, send inconsistent messages to the marketplace and fail to leverage scale economies. Silos can be monumentally inefficient and, worse, a major barrier to innovation, profitability and customer satisfaction.

Silos get busted when senior leadership sets unifying goals and promotes a reward structure that emphasizes co-operation and collective success.

Business unit leaders must understand the overarching goals of the total organization and the importance of working in concert with other areas of the business to achieve those crucial objectives.

Building trust

A collaborative team isn’t a group of people working together. It’s a group of people working together who trust each other.

Trust is the belief or confidence that one party has in the reliability, integrity and honesty of another party. It’s the expectation that the faith one places in someone else will be honoured. It’s also the glue that holds together any group and the foundation of true collaboration. Without trust, a team loses its emotional ballast.

In an environment of suspicion, people withhold information, hide behind psychological walls and withdraw from participation.

As a leader, you need people to trust you. But how do you show that you trust them? The way information is handled determines whether it becomes an obstacle to or an enabler of collaboration. Some leaders (who profess to value collaboration) undermine their effectiveness by withholding information or doling it out on a need-to-know basis. Others ask for input when what they really want is a rubber stamp for decisions already made.

Leaders build trust through honest and transparent communication, which is often trickier than it sounds. For example, it’s fine to emphasize the positive aspects of a situation, just be careful not to omit or sugar-coat the negative.

You may think you’re protecting people by doing so – but the signal you’re really sending is that you think they can’t handle the truth.

In an atmosphere of high trust, where communication is candid, goals are co-created, setbacks are analyzed for the purpose of learning (not blaming), and successes are celebrated and shared, people respond by taking ownership, becoming even more engaged and forthcoming.

And nothing builds trust faster in a leadership team (or any team, for that matter) than getting to know one another as individuals. When you hold offsite retreats or workplace events, be sure to create opportunities for social time to develop or deepen personal relationships. Reinforcing these relationships at the beginning of any new initiative will also increase effectiveness throughout the process.

Warming up their body language

There are two sets of body language cues that people look for in leaders. One projects warmth and caring, and the other signals power and status.

Both are necessary for leaders but, in your role as chief influencer, the warmer side of non-verbal communication (which has been undervalued and underutilized by leaders more concerned with projecting strength, status and authority) becomes central to creating the most collaborative workforce relationships.

The body language of inclusion and warmth includes positive eye contact, genuine smiles, and open postures in which legs are uncrossed and arms are held away from your body, with palms exposed or resting comfortably on the desk or conference table.

Mirroring is another non-verbal sign of warmth. You may not realize it but when you’re dealing with people you like or agree with, you’ll automatically begin to match their stance, arm positions and facial expressions. It’s a way of signalling that you’re connected and engaged.

Facing people directly when they’re talking is also crucial. It shows that you’re totally focused on them. Even rotating your shoulders a quarter turn away signals a lack of interest and makes the other person feel as if their opinions are being discounted.

Of course, giving others your complete attention when they’re speaking is one of the warmest, most inclusive signals you can send.

Valuing diversity

Experiments at the University of Michigan found that, when challenged with a difficult problem, groups composed of highly adept members performed worse than groups whose members had varying levels of skill and knowledge.

The reason for this seemingly odd outcome has to do with the power of diverse thinking. Group members who think alike or are trained in similar disciplines with similar knowledge bases run the risk of becoming insular.

Instead of exploring alternatives, they allow a confirmation bias to take over and tend to reinforce each other’s predisposition.

Innovation is triggered by cross-pollination. Creative breakthroughs occur most often when ideas collide and combine. And, by the way, innovative breakthroughs today aren’t taking place in a lab, but rather are a result of conversations with customers (internal and external), suppliers and outsiders who know enough about the problem to contribute, but bring a unique perspective.

As one GE executive put it, “Cross-functional teams are enhanced by outside experts who know enough to understand the terms of the question but not so much as to run into the same stumbling blocks as the subject experts. Chemical problems at GE are almost never solved by a chemist.”

Showing empathy

Development Dimensions International has studied leadership for 46 years. In its latest research with more than 15,000 leaders from more than 300 organizations across 20 industries in 18 countries, DDI looked at leaders’ conversational skills that had the highest impact on overall performance. At the top of the list was empathy – specifically, the ability to listen and respond empathetically.

In his book On Becoming a Person, psychologist Carl Rogers wrote, “Real communication occurs when we listen with understanding – to see the idea and attitude from the other person’s point of view, to sense how it feels to them, to achieve their frame of reference in regard to the thing they are talking about.”

A further discovery in the DDI report was that only four out of 10 leaders in their global study were proficient or strong in empathy. As a leader, if you already rank high in empathy, you gain a genuine professional advantage.

If not, empathetic listening is a skill worth developing.

Creating psychological safety

Humans have two primitive instincts that guide our willingness to collaborate – or not – and they are triggered under very different circumstance.

The instinct to hoard can be traced back to early humans hoarding vital supplies, like food, out of fear of not having enough. The more they put away, the safer they felt. Still today whenever we feel fearful, distrustful or insecure, the hoarding instinct kicks into high gear, urging us to hold on tightly to whatever we possess – including knowledge.

When insights and opinions are ridiculed, criticized or ignored, people feel threatened – and they typically react by declining to contribute further.

But humans are also learning, teaching and knowledge-sharing. According to evolutionary psychologists, this trait is also hard-wired, linking back to when humans first started gathering in clans. Leaders trigger the sharing instinct when they create psychologically safe workplace environments in which people feel secure, valued and trusted.

In the age of digital transformation, even high-tech companies need soft-skilled talent. In researching what makes teams successful, Google’s Project Aristotle found that psychological safety is key. Google’s most effective teams also exhibited “social sensitivity,” meaning that members spoke about equally (usually short and sweet) and were able to pick up on each other’s interpersonal cues, including body language.

Today’s corporation exists in an increasingly complex and ever-shifting ocean of change. As a result, collaboration is not a nice-to-have organizational philosophy. It’s an essential ingredient for organizational survival.

So leaders of collaboration (at all management levels) may need to redefine their roles and update their skills.

Columnist Carol Kinsey Goman, PhD, is an executive coach, consultant, and international keynote speaker at corporate, government, and association events. She is also the author of The Silent Language of Leaders: How Body Language Can Help – or Hurt – How You Lead.

© 2017 Distributed by Troy Media

The views, opinions and positions expressed by all columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of NetNewsLedger.