THUNDER BAY – MINING – Over time one of the critical factors in aviation across the north has been the danger of aircraft icing up. Ice on the wings or propellor has been a factor in countless incidents and accidents.

THUNDER BAY – MINING – Over time one of the critical factors in aviation across the north has been the danger of aircraft icing up. Ice on the wings or propellor has been a factor in countless incidents and accidents.

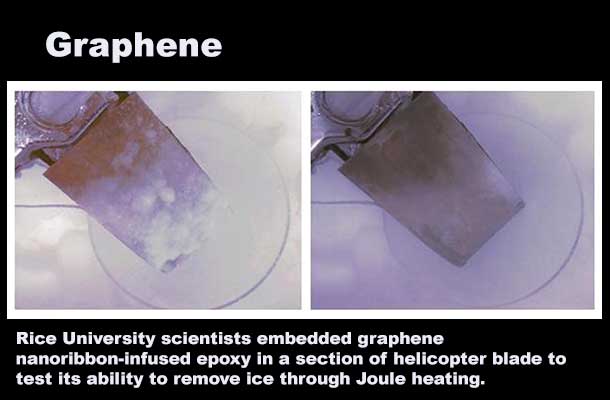

Now the latest research could be offering a solution to this problem, a thin coating of graphene nanoribbons in epoxy developed at Rice University has proven effective at melting ice on a helicopter blade.

The coating by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour may be an effective real-time de-icer for aircraft, wind turbines, transmission lines and other surfaces exposed to winter weather, according to a new paper in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

In tests, the lab melted centimeter-thick ice from a static helicopter rotor blade in a minus-4-degree Fahrenheit environment. When a small voltage was applied, the coating delivered electrothermal heat – called Joule heating – to the surface, which melted the ice.

The nanoribbons produced commercially by unzipping nanotubes, a process also invented at Rice, are highly conductive. Rather than trying to produce large sheets of expensive graphene, the lab determined years ago that nanoribbons in composites would interconnect and conduct electricity across the material with much lower loadings than traditionally needed.

Previous experiments showed how the nanoribbons in films could be used to de-ice radar domes and even glass, since the films can be transparent to the eye.

“Applying this composite to wings could save time and money at airports where the glycol-based chemicals now used to de-ice aircraft are also an environmental concern,” Tour said.

In Rice’s lab tests, nanoribbons were no more than 5 percent of the composite. The researchers led by Rice graduate student Abdul-Rahman Raji spread a thin coat of the composite on a segment of rotor blade supplied by a helicopter manufacturer; they then replaced the thermally conductive nickel abrasion sleeve used as a leading edge on rotor blades. They were able to heat the composite to more than 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

For wings or blades in motion, the thin layer of water that forms first between the heated composite and the surface should be enough to loosen ice and allow it to fall off without having to melt completely, Tour said.

The lab reported that the composite remained robust in temperatures up to nearly 600 degrees Fahrenheit.

As a bonus, Tour said, the coating may also help protect aircraft from lightning strikes and provide an extra layer of electromagnetic shielding.