Graphene is a one-atom thick Carbon Based Material

WASHINGTON – To technology insiders, graphene is a certified big deal. While a great deal of attention has been paid to the Northwestern Ontario ‘Ring of Fire’ chromite potential, the ‘Arc of Fire’ where several very promising graphite finds, including the Zenyatta Ventures Albany project is located have not seemingly generated the same level of excitement.

They should, graphene, which is a new compound derived from graphite is taking the technology world by storm with its incredible potential.

The one-atom thick carbon-based material elicits rhapsodic descriptions as the strongest, thinnest material known. It also is light, flexible, and able to conduct electricity as well as copper. Graphene-based electronics promise advances such as faster internet speeds, cheaper solar cells, novel sensors, space suits spun from graphene yarn, and more.

One project under research could see graphene added to paint that would turn painting your home or office building result in the potential for it to become a solar panel.

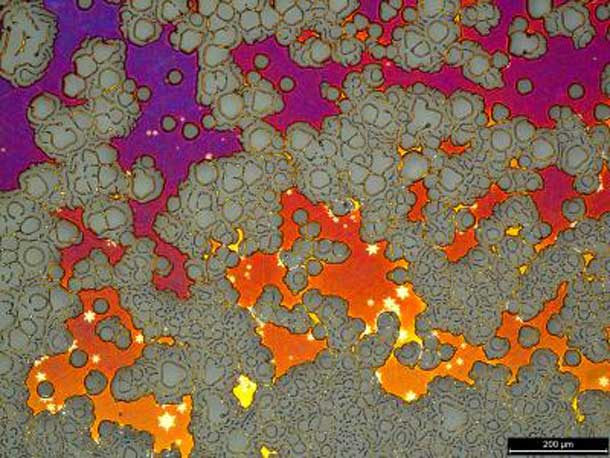

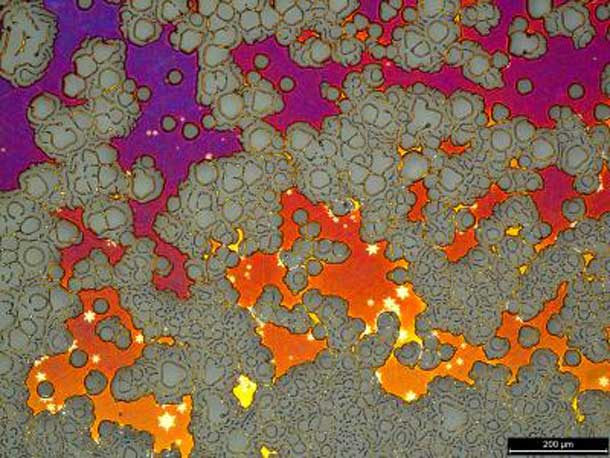

Now a research team at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Boulder, Colo., may help bring graphene’s promise closer to reality. While searching for an ideal growth platform for the material, investigators developed a promising new recipe for a graphene substrate: a thin film of copper with massive crystalline grains. The team’s findings appear in the journal AIP Advances, which is produced by AIP Publishing.

The key advance is the grain size of the copper substrate. The large grains are several centimeters in size – lunkers by microelectronics standards – but their relative bulk enables them to survive the high temperatures needed for graphene growth, explained NIST researcher Mark Keller.

The inability of most copper films to survive this stage of graphene growth “has been one problem preventing wafer-scale production of graphene devices,” Keller said.

Thin films are an essential component of many electronic, optical, and medical technologies, but the grains in these films are typically smaller than one micrometer. To fabricate the new copper surface, whose grains are about 10,000 times larger, the researchers came up with a two-step process.

First, they deposited copper onto a sapphire wafer held slightly above room temperature. Second, they added the transformative step of annealing, or heat-treating, the film at a much higher temperature, near the melting point of copper. To demonstrate the viability of their giant-grained film, the researchers successfully grew graphene grains 0.2 millimeters in diameter on the new copper surface.