Icebergs Reported Ahead as Officers and Lookouts Brace for a Busy Day at Sea

ABOARD RMS TITANIC, Early Morning – April 14, 1912 — A biting wind swept across the decks just after midnight this Sunday morning, the coldest yet since the Titanic departed Southampton. Gone is the gentle softness of Friday’s breeze — in its place, a crisp and bracing chill, sharp enough to redden the noses of early risers and crew alike.

The change in temperature has not gone unnoticed. As the ship continues westward into the colder currents of the North Atlantic, the talk among officers and engine hands has turned once again to the growing frequency of iceberg warnings — several of which were relayed yesterday through the ever-busy Marconi wireless room.

A SILENT SEA, AN UNUSUALLY STILL NIGHT

The sea remains calm — eerily so, say some of the more seasoned sailors. Not a ripple nor wave breaks the surface. The water is said to be like black glass, reflecting the stars so perfectly that some lookouts have reported brief confusion between sky and sea.

According to Second Officer Charles Lightoller, who finished his watch shortly before four bells this morning:

“The air has turned markedly colder. We’ve altered course slightly in accordance with the latest ice reports, but it’s clear we’re sailing nearer to the edge of the Labrador Current. It’s that current that carries bergs southward this time of year.”

He added with a smile, “But rest assured — the lookouts are sharp, and the ship handles beautifully in this air.”

MORE ICE WARNINGS VIA WIRELESS

Overnight, further messages were received from ships further west and north:

“Large bergs and field ice sighted near 42°N, 50°W. Proceed with caution.” – SS Noordam

“Pack ice and bergs extending for miles.” – SS Rappahannock, intercepted at 2:30 A.M.

The messages have been transcribed and sent to the bridge, and Titanic continues her steady course, now expected to reach the iceberg belt by late Sunday afternoon or evening.

Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, working long shifts due to passenger traffic, are said to be doing double duty — fielding a steady stream of private messages while ensuring critical navigation alerts are passed to command.

THE PASSENGERS SLEEP ON

In the lower corridors and saloons, little stirs at this hour. Stewards quietly prepare breakfast trays, and the last of the late-night bridge players in the First Class lounge have retired to their cabins.

A handful of early risers — bundled in furs and shawls — have ventured onto the promenade to take in the dawn. One gentleman remarked to this reporter, “It feels like Canada has come to greet us.”

The breath fogs in the air, and the horizon, still hidden in night, waits to reveal whether today will bring sun or frost.

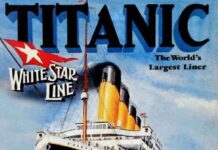

THE SHIP, UNBOTHERED

Despite the chill and quiet warnings from beyond the horizon, the Titanic sails on with confident poise. Her four great funnels stand tall against the starlit sky, and her engines — deep in the heart of her hull — beat with the rhythm of purpose.

This morning feels still — not uneasy, but watchful. The kind of stillness that speaks of nature holding its breath.

Whether the day will pass without note, or write itself into the ship’s story, remains to be seen.