From systemic discrimination to lateral violence within Indigenous communities, the fight for justice continues

A Legacy of Discrimination that needs to end in Thunder Bay and across Canada

Indigenous people in Canada continue to face racism, systemic discrimination, and the lasting trauma of colonial policies such as the Indian residential school system.

These challenges persist in nearly every aspect of life—interactions with law enforcement, the legal system, public spaces, housing, banking, and healthcare. Despite government commitments to reconciliation, many Indigenous communities still face barriers to justice and equality.

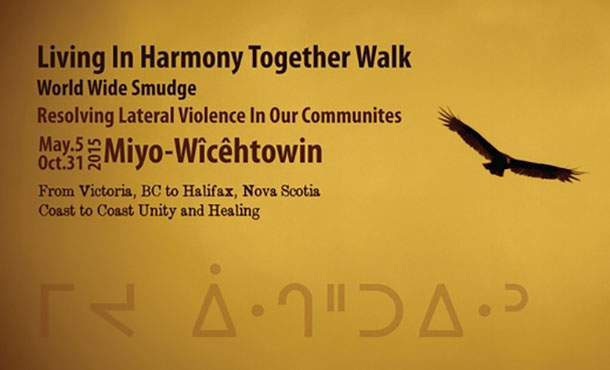

However, another critical issue often left unspoken is lateral violence—the internal discrimination, bullying, and power struggles that exist within Indigenous communities, especially against women.

Many Indigenous individuals, particularly women, face mistreatment from their own leadership, including Chiefs, Councils, and Band Offices, where power imbalances and colonial legacies continue to play out in harmful ways.

Distrust in Police and the Legal System

One of the most pressing issues is the fraught relationship between Indigenous people and law enforcement. Decades of mistreatment, racial profiling, and cases of police violence have led to a deep mistrust of authorities by Indigenous youth.

Instead of building trust, seeking equality and reconciliation, sadly all too often the legal system seems to treat Indigenous people, especially youth like the raw materials in a legal factory that only works to serve itself.

High-profile incidents, such as the deaths of Indigenous individuals in police custody, have reinforced these concerns.

The legal system also presents significant challenges.

Indigenous people are disproportionately represented in Canada’s prison population, often due to systemic racism, poverty, and over-policing.

While courts have recognized the need for alternative sentencing under the Gladue principles—intended to address the unique circumstances of Indigenous offenders—many argue that these measures are not widely or effectively implemented.

In Thunder Bay while there is an Indigenous court in the Superior Court of Justice the real process is not really one that is seen as solving the issues, but rather another legal assembly line building criminal records.

It might be ironic but in Thunder Bay the Superior Court is at the corner of Brodie and Justice Avenue, and Justice Avenue is a one way street. Many Indigenous people agree with that sentiment as a sad reality.

The Struggle to Search for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) continues to devastate families and communities across Canada. Indigenous women face violence at disproportionately high rates, yet investigations into their disappearances and deaths are often slow, incomplete, or ignored altogether.

A current example of this failure is the struggle in Winnipeg to search the Prairie Green landfill for the remains of Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran—two of four Indigenous women murdered in 2022 by a convicted serial killer. Despite calls from families, Indigenous leaders, and human rights advocates, the Manitoba government initially refused to fund the search, citing safety concerns and costs.

This decision sparked outrage, as it symbolized how Indigenous lives are devalued by the justice system. After immense pressure, a federal-provincial agreement was reached to conduct a feasibility study, but delays in seeking real justice continue to frustrate those seeking justice.

Lateral Violence: A Hidden Crisis in Indigenous Communities

While external discrimination is a major issue, lateral violence—when Indigenous people mistreat or oppress their own community members—is another deeply rooted problem.

This can take the form of bullying, harassment, exclusion, and abuse of power within Band Offices, Chief and Council structures, and community leadership. Often it appears the very concept of reconciliation isn’t practiced in the Band Office on reserve.

In addition there is often major differences in the treatment of on-reserve and off-reserve members.

Indigenous women, in particular, often bear the brunt of lateral violence. Many have reported being silenced, ignored, or even targeted by their own leaders when they speak out about corruption, abuse, or gender-based discrimination within their communities. Band Councils and Chiefs, in some cases, use their positions of power to intimidate those who challenge them, preventing true progress and accountability.

This issue is a direct result of colonialism, which disrupted traditional governance systems that once valued matriarchal leadership and community harmony.

The Indian Act and federal interference created hierarchical, male-dominated leadership structures that have led to ongoing oppression within Indigenous communities.

Despite lots of talk at the national political level, there has been no real move to replace the Indian Act.

How Lateral Violence Harms Indigenous Communities

- Silencing of Women: Indigenous women advocating for justice are often dismissed or punished by their own leadership.

- Lack of Accountability: Corruption and favoritism in Band Offices prevent fair access to housing, jobs, and resources.

- Divided Communities: Instead of unity, lateral violence creates divisions, making it harder to fight for Indigenous rights as a collective.

Retail Racism: The Reality of Racial Profiling

Shopping while Indigenous often means being followed by security, wrongly accused of theft, or treated with suspicion. This form of racial profiling is a daily reality for many Indigenous people, further reinforcing feelings of exclusion and discrimination. The recent cases of wrongful detainment in major retail stores highlight the urgent need for anti-racism training and stronger policies against discrimination in businesses.

Racism on Public Transit

Indigenous people also face racism while simply trying to use public transit. Reports from cities like Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Vancouver have documented cases where Indigenous passengers were harassed by both other riders and transit staff. Indigenous women, in particular, have reported feeling unsafe on public transit, with some being targets of verbal abuse and physical violence. In some cases, transit police or security have been accused of unfairly targeting Indigenous riders for fare enforcement while overlooking non-Indigenous passengers.

Barriers in Housing, Banking, and Healthcare

Accessing essential services such as housing, banking, and healthcare is another challenge. Indigenous individuals frequently encounter discrimination when trying to rent homes or open bank accounts, with landlords and financial institutions viewing them as “high risk” due to harmful stereotypes. In healthcare, Indigenous patients have reported experiencing neglect, racism, and substandard treatment—sometimes with deadly consequences, as seen in the tragic death of Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw woman who recorded racist remarks by hospital staff before her passing in 2020.

Jordan’s Principle: A Lifeline That Still Fails Too Many

One of the most important policies meant to ensure Indigenous children receive the services they need without jurisdictional delays is Jordan’s Principle.

Named after Jordan River Anderson, a Cree child from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba, the principle was created to prevent Indigenous children from being caught in government disputes over funding for essential services. Jordan spent his entire short life in a hospital while the federal and provincial governments argued over who should pay for his at-home care.

He died at the age of five without ever living in a home environment. In response to his tragic case, Jordan’s Principle was established to ensure that First Nations children receive healthcare, education, and social services immediately, with funding disputes resolved afterward.

However, despite being legally binding, Jordan’s Principle continues to fail many Indigenous children. The system remains bureaucratic and difficult to navigate, with families often facing excessive paperwork, long approval times, and denials for critical services.

Many Indigenous children with disabilities or special needs are left waiting for essential medical treatments, therapy, and supports that non-Indigenous children receive without question.

In some cases, funding requests are outright rejected due to unclear criteria, leaving families with no recourse but to fight lengthy appeals processes while their child suffers.

Another major failing of Jordan’s Principle is that it does not consistently apply to Métis and Inuit children, leaving many Indigenous youth without equitable access to services.

Although the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has repeatedly ruled that the federal government must fully implement Jordan’s Principle, reports show that Indigenous children still face gaps in services, underfunding, and systemic barriers. Instead of fulfilling the promise of ensuring Indigenous children receive the same level of care as all other children in Canada, the principle is often undermined by government inaction, funding shortfalls, and systemic racism within service delivery.

For Jordan’s Principle to truly succeed, the government must simplify the application process, eliminate unnecessary delays, and provide automatic approvals for urgent cases.

There must be stronger oversight and accountability measures to ensure Indigenous children receive timely, culturally appropriate care without being forced to fight for their basic rights.

Without these changes, Jordan’s Principle remains another example of a policy designed to help Indigenous people but failing in execution—another unfulfilled promise in Canada’s long history of systemic discrimination.

So What Are the Solutions?

While the issues are complex, meaningful change is possible. Solutions must be systemic, long-term, and led by Indigenous voices.

1. Police Reform and Accountability

- Increased Indigenous representation in law enforcement.

- Mandatory cultural competency and anti-racism training for officers.

- Independent oversight bodies to investigate police misconduct.

2. Justice for MMIWG and Families

- Full-scale searches for missing Indigenous women, including landfills.

- A national task force with Indigenous leadership to oversee MMIWG cases.

- Increased funding for Indigenous-run victim services and crisis support.

3. Addressing Lateral Violence in Indigenous Communities

- Greater accountability for Chiefs and Councils.

- Women-led governance initiatives to restore balance.

- Education programs to decolonize leadership and rebuild trust.

- Stronger protections for whistleblowers in Band Offices and governance structures.

4. Anti-Racism Policies in Retail, Transit, and Services

- Mandatory training for employees in anti-racism and Indigenous cultural awareness.

- Clear policies against racial profiling with consequences for violations.

- Stronger consumer protection laws to address discrimination in businesses and public transit.

5. Equal Access to Housing, Banking, and Healthcare

- Stricter enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in housing and financial services.

- Indigenous-run financial institutions and housing initiatives.

- Culturally safe healthcare services with Indigenous-led programs.

Conclusion

Indigenous people in Canada should not have to fight for basic human rights. Systemic racism and lateral violence must be acknowledged and dismantled, not only by governments but by every institution—including Indigenous governance structures.

True reconciliation means ensuring justice, respect, and equal opportunities for Indigenous communities. Addressing these ongoing challenges requires both policy changes and a shift in societal attitudes—because equality is not a privilege; it is a right.