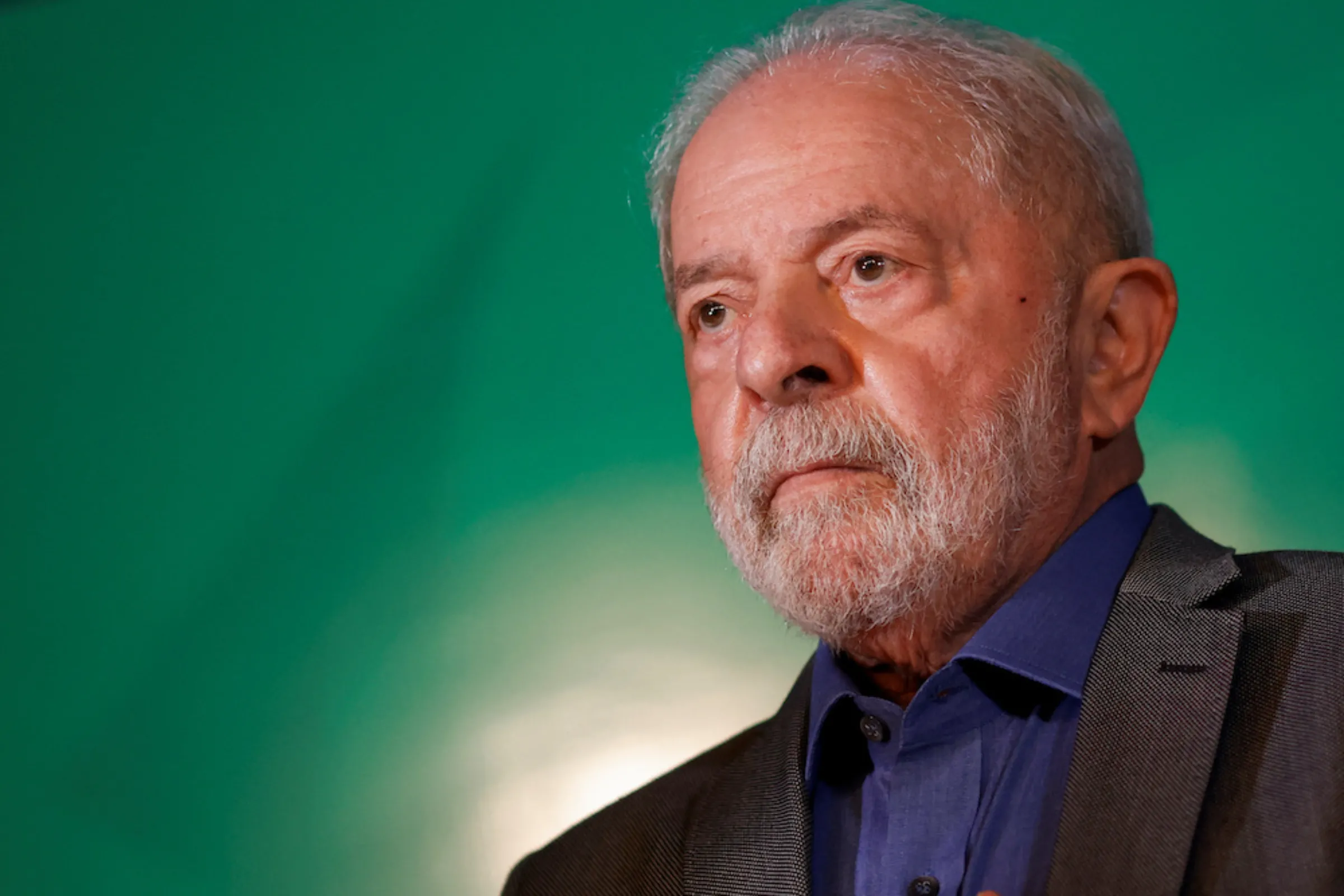

Protecting Amazon rainforest and tackling climate change are key issues for Brazilian President-elect Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva

- Far-right president Jair Bolsonaro to step down in January

- Lula may revoke many anti-environmental measures by decree

- Climate policy think-tank says over 100 could be scrapped

RIO DE JANEIRO – As Brazil prepares for leftist President-elect Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva to replace far-right leader Jair Bolsonaro in January, voters are asking: How many of the incumbent’s environmental policies could Lula undo? And how long might it take?

The answers, green experts say, could be plenty – and not long.

After Lula won the election in October, his Workers Party (PT) started to map all of the decrees issued by Bolsonaro and the regulations enacted under his administration, in order to decide which ones should be revoked by the incoming government.

Bolsonaro’s administration has been criticized by advocates for removing environmental protections and weakening federal environmental and indigenous agencies – resulting in increased deforestation and reports of invasions of indigenous lands.

But many such decisions by his government were simple decrees and regulations that experts say can be swiftly revoked.

A study by climate policy think-tank Talanoa cited 107 measures – relating to the environment, nature and green issues – adopted during Bolsonaro’s four years in office, which it said should be immediately repealed when Lula takes power.

Here are five key ways in which environmental advocates believe Lula’s administration could – with the stroke of a pen – strengthen climate, nature and indigenous policies in Brazil.

Ease collection of environmental fines

A set of Bolsonaro administration decrees altered how the Brazilian government deals with environmental fines, which has hugely slowed down the process, according to Talanoa.

For instance, a “reconciliation” process was established that allowed people who are penalized for deforestation or other environmental violations to negotiate the fines.

A backlog of thousands of fines has since amassed, according to internal documents seen by Reuters and government sources.

Less than 2% of fines issued by Brazil’s environmental authority Ibama for violations in the Amazon region in 2021 were actually agreed upon through the reconciliation process and levied, government documents show.

The Climate Observatory, an environmental watchdog, has described the process as “unnecessary and delaying” – and recently urged the incoming government to scrap it.

Ibama previously said the “reconciliation hearings” are meant to process fines more quickly, reduce bureaucracy and generate savings.

Restore scope of indigenous affairs agency

Funai, the indigenous affairs agency, narrowed the scope of its work under Bolsonaro’s administration, after many of its posts were given to people loyal to the incumbent president.

This attracted criticism from activists who said the appointments went against the institution’s mandate.

In 2020, Funai issued a regulation stating that it would no longer assist all indigenous peoples in the country and only help those living in areas formally recognized by the Brazilian government as indigenous lands.

Estimates suggested that the policy affected more than 230 indigenous territories still in the process of being recognized.

Funai has previously stated that requests to protect unrecognized areas were “unreasonable” because much of this land is under private ownership rather than belonging to the state.

Sesai – the Ministry of Health’s indigenous health service – has come under fire from native groups who say it has not given adequate assistance, which was cited as a major problem during the COVID-19 pandemic, with high mortality in indigenous areas.

Indigenous leaders have called on Lula to not only re-establish the previous, wider scope of Funai and Sesai but to also resume the process of formally recognizing more indigenous territories. Bolsonaro refused to do so during his presidency.

Revoke support for small-scale mining expansion

In February 2022, Bolsonaro signed a decree that created the Support Program for the Development of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining, a move that environmentalists denounced as promoting illegal mining in the Amazon rainforest.

Illegal gold mining is a major driver of deforestation and invasions of indigenous lands, as miners enter protected areas, cut down trees and then burn them to set up their operations.

Mining also leads to the contamination of waterways and land with mercury, a toxic substance used in the mining of gold and linked to poisoning of indigenous communities.

In a statement when the decree was signed, the government said its aim was to formalize the mining, encourage best practices and improve the lives of the communities involved.

The Lauro Campos and Marielle Franco Foundation, a think-tank linked to Brazil’s Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), has said the mining decree should be scrapped completely.

“(The decree) represents yet another action made by the federal government without any concern for traditional peoples and communities, and the environment,” the think-tank wrote in a paper listing measures the Lula administration could revoke.

Strengthen committees weakened under Bolsonaro

In April 2019, a Bolsonaro decree disbanded most government committees and working groups across ministries and key issues – although some were later re-established with new members.

Two of the dismantled committees were linked to an Amazon preservation fund that received donations from Norway and Germany. The so-called Amazon Fund, which contains 3.2 billion reals ($617 million) for rainforest protection, was frozen.

In the case of the committees linked to the Amazon Fund, then environment minister Ricardo Salles said there were irregularities with the way the funds were being released.

“Bolsonaro could have saved these committees if he was interested in maintaining the (Amazon) fund,” said Natalie Unterstell, president of Talanoa. “But he didn’t.”

In early November, Brazil’s Supreme Court ordered the Bolsonaro administration to reactivate the fund, and gave it 60 days to do so. The government has not complied with the order.

Germany’s development ministry last month said it was open to unfreezing payments, while Norway’s environment minister said more recently that the fund would restart in early 2023.

However, Lula should look beyond just these two committees and expand the effort to rebuild more of what Bolsonaro dismantled, according to Unterstell.

That includes Conama – the National Committee on the Environment – which, among its responsibilities, weighs in on climate policy, decides on regulations for public and private projects, and is the final arbiter on fines issued by Ibama.

Bolsonaro-era decrees reduced the number of voting members of Conama, sidelining non-profits and experts from outside of government – something Lula could now reverse, Unterstell said.

Remove ‘gag orders’ on civil servants

ICMBio, one of the two main federal environment protection agencies in Brazil, issued an update to its code of conduct during the Bolsonaro administration that restricted what information ICMBio employees are permitted to make public.

This barred them from publishing articles, research documents and studies without authorization from ICMBio.

“This had a huge impact, because many public servants in those areas are also researchers” said Adriana Ramos, an advisor at Instituto Socioambiental, an environmental non-profit.

The publishing ban and other internal changes at the Ministry of the Environment, ICMBio and Ibama have been widely criticized by green activists – and Talanoa described the measures as a “gag order” on public servants.

Fernando Vianna, president of the INA association of Funai employees, said earlier this year that there was a climate of “fear” and “persecution” among officials working in the agency.

Revising those rules could restore autonomy to environmental officials, and improve staff morale, according to insiders.

(Reporting by Fabio Teixeira; Editing by Kieran Guilbert and Megan Rowling)