Solar-powered boats are helping indigenous groups travel on their Amazon river highways faster, cheaper and more cleanly

By Melissa Godin

TENA, Ecuador – (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Ecuador’s rainforest Achuar people say their ancestors long dreamed of a “fire canoe” or “electric fish” that would let them move swiftly along the region’s winding rivers, to more easily reach other distant Achuar communities in the largely roadless jungle.

Now, the arrival of solar-powered boats is turning an old myth into a modern reality.

Three solar boats – an Achuar design topped with protective roofs covered in solar panels – now ply a 67-kilometre (40-mile) stretch the Pastaza and Capahurari rivers in Achuar territory, connecting nine indigenous communities.

The craft have allowed communities without previous access to motorized boats to travel more swiftly, and others that had been using diesel engines to cut costs, move quietly and better protect their waterways from pollution.

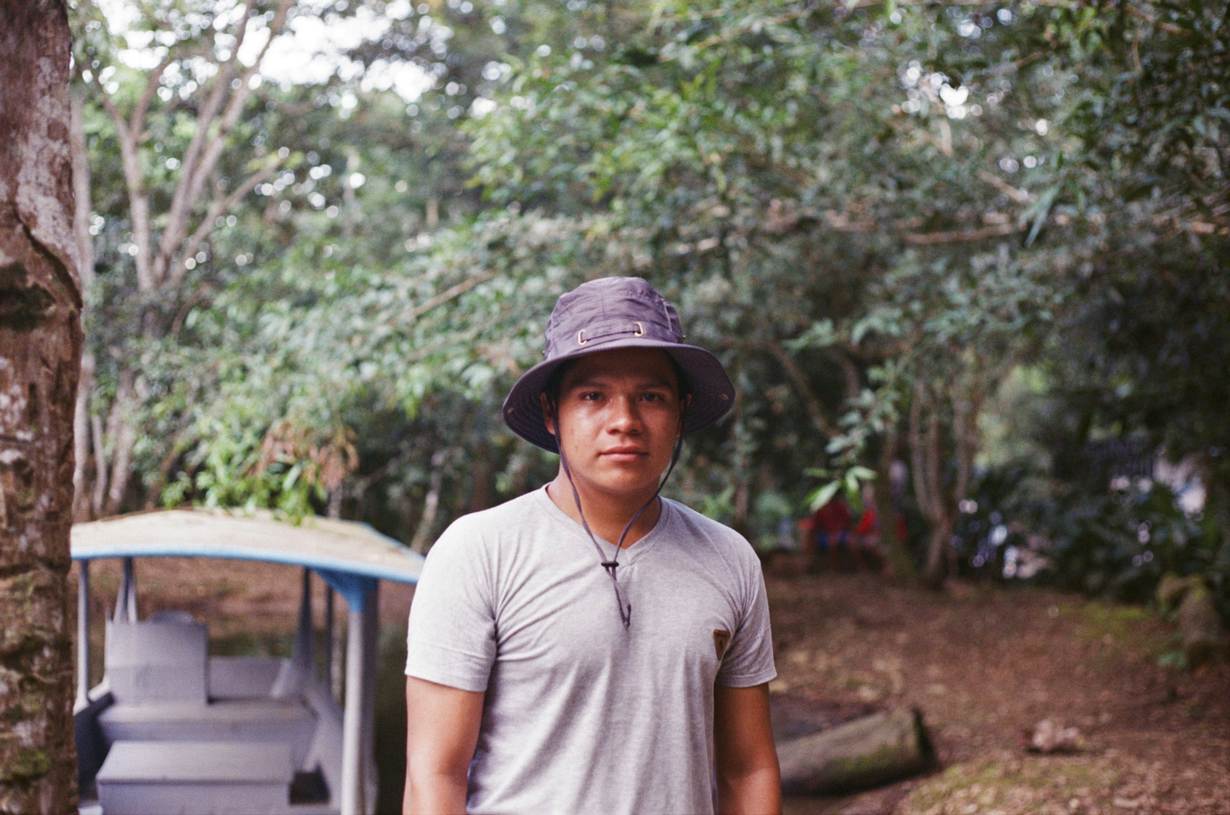

“The solar-paneled canoes have been a huge help in connectivity, especially for the most (economically) vulnerable families,” said Oscar Mukucham, 22, who saw a first pilot solar canoe as a teenager and now is employed building them for Kara Solar, the manufacturer.

“We have this dream as Achuar people to conserve our waterways,” he added. “The boats are a huge connective force in our lives.”

Oliver Utne, the founder of Kara Solar, a solar-powered river transport, energy and community enterprise in the Amazon, said the idea for the solar craft emerged about a decade ago.

“We initially started talking about solar-paneled boats as a joke,” he said. “We just thought it would be too technically challenging.”

But when Utne, an American, traveled home to the United States in 2013, he met with professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) who carried out a feasibility study.

They said that with the right batteries the canoes could work.

Today the boats, which carry up to 20 people and cost $30,000 to $40,000 each to build, use roof solar panels to collect power, which is stored in a battery.

A fully loaded craft can travel at speeds of 15-20 kilometers per hour (9-12 miles per hour) for 60-100 km (37-60 miles) on a full battery charge, Utne said.

Funding to provide the riverboats free of charge to indigenous communities has come from U.S.-based philanthropies focused on tech, sustainability and indigenous land protection.

The boats, built by indigenous people in collaboration with Kara Solar, have allowed the communities to move critical supplies and access services over a wider area.

With a swifter and cost-free way to travel, Achuar groups can also afford to travel more for pleasure, Mukucham said.

The solar boats also have allowed indigenous communities to more easily, frequently and inexpensively patrol their land for invasions by illegal loggers.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the provincial government built a new road into Achuar territory, spurring a “balsa boom” as outsiders arrived to cut balsa trees, whose wood is used in the manufacture of wind turbines.

The Sharamentsa Achuar have used their solar-powered canoes to monitor their stands of balsa and identify those illegally harvesting wood, Utne said.

That is key as Ecuador’s Amazon region faces worsening deforestation pressures as a result of expansion of mining, oil drilling and logging, and as indigenous communities step up efforts to protect their land.

Since the turn of the century, Ecuador has lost about 900,000 hectares of tree cover, a 4.7% decline, according to Global Forest Watch – the equivalent of 1.6 million football pitches.

FROM MYTH TO MANUFACTURING

The introduction of solar canoes in Achuar territory has been particularly apt as it marries traditional culture and modern technology, backers say.

In the Achuar worldview, dreams shape people’s vision of the world and inform how they should behave in the future – and Achuar tales passed down from ancestors have long spoken of a future with “fire canoes” or “electric fish” as transport.

When solar canoes were first discussed, “it was clear that something in the Achuar myths was seen as connected to this project,” Utne said. “People would say, ‘Oh yes, I’ve seen this in a dream.’”

His firm’s name – Kara Solar – comes from the Achuar term for “a dream that is coming true”.

Utne’s firm hopes see its solar canoes eventually used in broader areas of the Amazon, a region where river transport is far more common than road travel.

The company has philanthropy-backed projects under development in nearby Brazil, Suriname, French Guiana and Peru, and as far away as the Pacific’s Solomon Islands, in each case with indigenous groups sharing designs and technology, Utne said.

“It is about indigenous-to-indigenous training,” said Mukucham, who helps build the Achuar canoes. “Our dream is to spread this and strengthen this capacity within other communities.”

Utne said he’s aware that manufacturing solar panels requires mining rare metals – something that can be a threat to indigenous forests.

But “for us the question is, ‘If these resources are going to be mined, how should we put them to use?’” he said. “We think a solar-panelled boat transporting people along the river of their territory is as good a use as there can be.”

Reporting by Melissa Godin ; editing by Laurie Goering : Credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation