Jody Wilson-Raybould is the independent member of Parliament for the British Columbia riding of Vancouver Granville and the author of From Where I Stand: Rebuilding Indigenous Nations for a Stronger Canada. Her memoir, “Indian” in the Cabinet: Speaking Truth to Power, will be published later this year.

Lowering the flag is not enough. Symbolism will not bring back the precious children of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. It will not replace the lives these 215 children would have led – their achievements, their happiness, the contributions they would have made to this world.

Lofty rhetoric and mournful platitudes will not change the laws, policies and practices of governments that have resulted in the violations of the human rights of Indigenous peoples in the past and continue to do so today. We need deliberate, coherent and intentional action.

We need leadership that results in bold, transformative change. Leadership from people – from Canadians – when they stand up and demand action. And leadership from those we elect and, in particular, from those at the top.

We have one of these, but not the other.

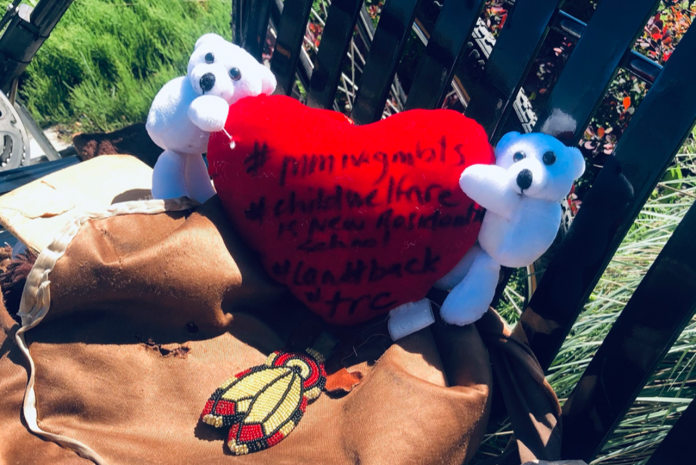

The reaction of Canadians to reports of unmarked graves of 215 Indigenous children on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School at Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has been important. Most Canadians recognize that this is not “news.” We all know the history of our country includes atrocities suffered by Indigenous peoples. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) held hearings over six years, and featured testimony from more than 6,500 witnesses, including residential school survivors. The TRC produced an entire volume on missing children and unmarked burials that stated there were at least 3,200 registered deaths of children in the schools, but the stories of survivors tell us the actual numbers are much higher. The inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls brought even more vital evidence to light.

Yes, there remains more we must do. Thankfully, many Canadians are demanding to learn more. This is good. But this learning must be done on the terms of the survivors. It is for the descendants of the children – including any living siblings, parents or even grandparents – and for their community to guide what happens next. They will let us know what we must do. Just as we all do when our loved ones leave us, and must be honoured and remembered.

We have to continue learning from the survivors. In recent months, I have had the opportunity to listen to recordings of my grandmother, who passed away in 1999, reflecting on her experience at St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay, B.C., which she was forced to attend in the early 1930s. While there, she experienced violence. She was also so difficult, and such a challenge to the school authorities, that they kicked her out. She was lucky; she escaped. Her resilience helped theresurgence of our people, the Kwakwaka’wakw. I have learned so much from her, and from so many of our people who continue to show the way.

But in addition to wanting to learn, Canadians are increasingly demanding change – real change. From coast-to-coast-to-coast, I’m hearing Canadians ask what they can do, and what our leaders must do.

Enough with tolerating systemic racism. Enough with incremental half-measures. Enough with denying Indigenous rights and fighting our peoples through the courts. Enough with setting up endless negotiation processes that do not lead to change on the ground. Enough with the abhorrent rates of Indigenous children in care, overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, youth suicide, homelessness and poverty, and lack of clean drinking water.

Enough!

Canadians understand that what allowed the creation of residential schools and unmarked graves was laws, policies and practices that failed to recognize and implement the basic rights of Indigenous peoples – and that what is needed is for these laws to be transformed. Calls to do so have been made for decades. Government after government has failed to act. The current government said – they promised – that they would finally do this work. Hypocritically, and shamefully, that work was abandoned.

This is a failure of leadership. On addressing the legacy of colonialism, as with many other issues, our leaders have not done what is required. They typically choose to do what is easy over what is right, political expedience over policy change, and appearance over substance.

When it comes to Indigenous peoples, our government privileges rhetoric over real action. They have spent more time trying to figure out how to “spin” what they have done and convey a sense of accomplishment to Canadians than actually delivering change. This is what they have done with the 94 Calls to Action of the TRC, where very few of the fundamental changes called for have been made more than five years later.

A word that appears again and again in the Calls to Action is “implement” – in particular, implementation of the basic human rights outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Implementation is about change on the ground – in the actual lives of Indigenous children, families and communities. It is about creating a social reality where human rights are upheld through laws, policies and practices that make it impossible for a child to be without clean drinking water, let alone the tragedy of dying, violently, neglectfully in a government institution, away from family and community.

There should be no confusion: Implementation has not happened. Bill C-15 (UNDRIP), if it is passed by Parliament in the coming weeks, does not implement the human rights of Indigenous peoples. The bill says the government will take action to develop a plan to implement them.

Anyone in government who tells you differently does not understand their own legislation. At best, it will push future governments to do new things, and make it harder for them to do so little – unlike this federal government and the ones before.

Remember, the residential school system was based on the Indian Act, which did not explicitly say the children in those institutions should be abused, malnourished, used for medical experimentation, banned from learning their culture, language and identity, and sometimes killed. All the Indian Act had to do was create those schools and a system to support them – and then all of those harms followed. This is how systemic racism and colonialism work.

Well, the Indian Act remains with us, and while the residential school sections may have been removed, it continues to impose colonial structures on Indigenous peoples, including a system of band council governance and the creation of reserves. This imposition is at the root of many present-day harms, disempowering Indigenous peoples, alienating long-standing Indigenous customs, law and traditions, reinforcing forms of gender discrimination, and limiting the ability of Indigenous peoples to care for their citizens as they must.

The Indian Act, a colonial statute that is almost 150 years old, remains the primary instrument governing the lives of the vast majority of First Nations in Canada. This government has done little to address or dismantle this reality, even after the Prime Minister promised to do so – in a historic Feb. 14, 2018 speech in the House of Commons – by developing and implementing an Indigenous rights recognition framework.

To be clear, this pattern of lacking leadership is not limited to Indigenous issues. Nor is it limited to a single leader or particular political party. In the same week Canada learned about the 215 children in Kamloops, we saw members of Parliament sit mute and accept the idea of a unilateral amendment to our Constitution rather than debate critical constitutional and legal questions about the future of our federation. We have a crisis of leadership throughout our system because of excessive partisanship.

Honouring the children means acting. Canadians know this now more than they have before – and we can do what is needed.

The question is: Will our leaders lead? Will our leaders honour the children?