WINNIPEG – OPINION – On January 31, the Canada Revenue Agency froze the Thunderbird House’s bank account.

“We were doing so well and on top of our bills, finally,” Thunderbird House Board co-Chair Richelle Scott called to inform me, “then this.”

Thunderbird House owes, including debt and penalty charges, nearly $100,000 from decade-old debts. With new supporters, a capable accountant, and a focused board of directors, Thunderbird House was in the final stages of obtaining a loan to pay it all off.

Now, their cheques are bouncing – with, ironically, the final rejected one written to the CRA.

The board is now scrambling to negotiate a deal and running out of time. Other bills are piling up and they can’t access funds to pay them. Almost no income is coming in as staff can’t be paid and volunteers are hard to find.

“We’re now at a standstill,” says Scott.

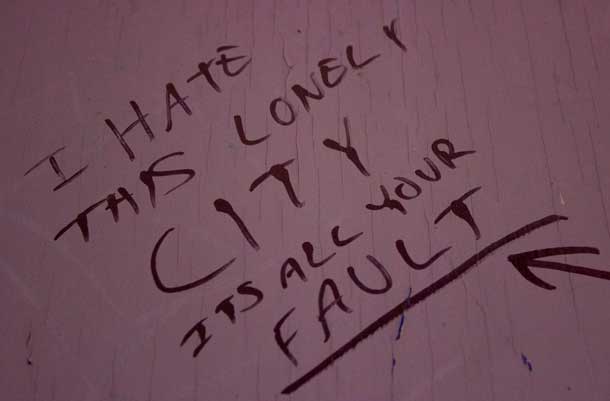

Winnipeg’s North End and downtown has struggled in the past but has reached it’s “tipping point.” Organizations and spaces that for decades kept the central core of the city safe and alive are falling apart, closing, or cut to the bare minimum.

Activists and community leaders are fighting a losing battle while new condos, businesses, and gentrification take over the downtown.

Reports emerged last week that one of Winnipeg’s oldest institutions, the 61-year-old Indian and Métis Friendship Centre, had been ransacked and looted. It had been closed for months after dwindling funding and troubles with its board of directors. Once serving 7,000 vulnerable people a month with a food bank, parenting services, and cultural programs – not to mention providing employment and investment – the IMFC’s future is now very much in doubt.

“It was a warm place to go,” says Albert McLeod, a North End elder and activist, “and those places are disappearing. There are almost no safe places left.”

Winnipeg’s most vulnerable are under attack

A recent decision by the City of Winnipeg to install strict security measures at the Millennium Library effectively cuts those who live on the street out of the space.

The new measures begin Monday and feature uniformed security checking bags and patrons with a metal detector. Items such as weapons are then confiscated, and illegal items reported to police. No place is provided to store items or bags.

Weapons shouldn’t be in libraries, of course, but the reality is that if you live on the street you likely need a weapon to survive.

“I know a First Nations grandmother living in a shelter who sleeps with a hammer under her pillow and a hatchet by her side,” McLeod told me. “Violence is a reality of life.”

If you live on the street, a library is a lifeline. It’s free, warm, and a safe place that provides essential services like the internet and access to things like a newspaper.

I called Ed Cuddy, manager of library services, to ask if he knew the Millennium Library’s new security rules will effectively prevent many homeless from accessing one of their most important resources in the city.

He explained that the new rules are meant to “reduce risk” and pointed to the fact the Millennium library is one of the only in Canada to have social workers.

Then, Cuddy admitted: “The reality is that the vulnerable may now have a harder time accessing the library.”

I asked him if a locker system or some kind of bag-check system could be instituted.

“We’re looking at that.”

Niigaan Sinclair

Niigaan Sinclair

Originally appeared in the Winnipeg Free Press on February 22, 2019. Republished with the permission of the author