THUNDER BAY – INDIGENOUS – In April 1847, a man named Wetus was among a group of Cree people who were converting to the Anglican faith in a gathering near what is now The Pas.

After a sermon by Rev. Henry Budd, the missionaries demanded any who wished to convert must give up their traditional ways, take a Christian name, have their ceremonial materials confiscated, and be baptized.

Wetus (subsequently named Louis Constant) gave Budd a Midéwiwin (Grand Medicine Society) scroll, written on birch bark and centuries old. It passed through several hands and was later reproduced in an 1851 book in England.

Under the direction of elders, the scroll has been interpreted to be a recreation of a Creation Story, a narrative that told Wetus’s community who they are, why they are here, and where they are going.

The scroll is also geographical, a kind of map depicting several interconnected lodges of Anishinaabeg and Cree communities, ceremonies, and who they relate to. It also contains stories of love and commitment and a tale of prophecies and beauty. It is both fiction and non-fiction — as most sacred texts are.

It is one of the most important and original texts of Manitoba.

Graphic writing is the oldest writing in the world. Dating to the first images made by human hands in cave paintings, moldings, and textiles, there have been million of texts throughout time that combine words, images, and sequential images to tell stories.

Graphic writing was used by Indigenous peoples to communicate amongst themselves, with non-Indigenous peoples, and with entities such as animals and spirits.

One of the best-known examples: the Maya, who were literate and had books (called codices) that combined pictures, graphs, and language.

When the Spanish encountered the Maya, they felt so threatened by their literacy they immediately burned every codice they could find. The colonization of the Americas was not just an invasion, but one of instilling illiteracy.

In Manitoba, we have a virtual archive of Indigenous graphic writing, found in rock paintings in the North, petroforms in Manitou Api, and beadwork almost everywhere. All of these incorporate graphic images, stories, and are the foundation for alphabetic forms of expression in novels and poetry today.

Over the past few decades, many Indigenous storytellers have turned back to graphic writing to speak about contemporary experiences. This has resulted in an explosion of graphic novels by Indigenous storytellers and artists, including Michael Yahgulanaas, Patti LaBoucane-Benson, Jay Odjick, Arigon Starr, Richard Van Camp, Steve Keewatin Sanderson, and myself.

Canadian publishers such as Renegade Entertainment, House of Anansi Press, and even comic book giants Marvel and DC now use Indigenous comic creators. Marvel even introduced a new superhero named Amka Aliyak, alias Snowguard, an Inuit teenager from Pangnirtung, Nunavut.

There is an Indigenous Comic Con held annually in November in Albuquerque, N.M.

At the centre of this surge sits Winnipeg.

The primary publisher of Indigenous graphic novels in the city is HighWater Press, a publishing division of Portage & Main Press. It has published more than two dozen graphic novels by Indigenous authors in the past 10 years — making it one of the largest publishers of Indigenous literature in Canada.

HighWater writers include David Robertson, who has more than 20 graphic novels and a Governor General’s Award for young people’s literature to his name. Robertson will join more than a dozen Indigenous artists and storytellers to produce the anthology This Place, a comic that retells Canada’s history through Indigenous experiences. It will be available in May.

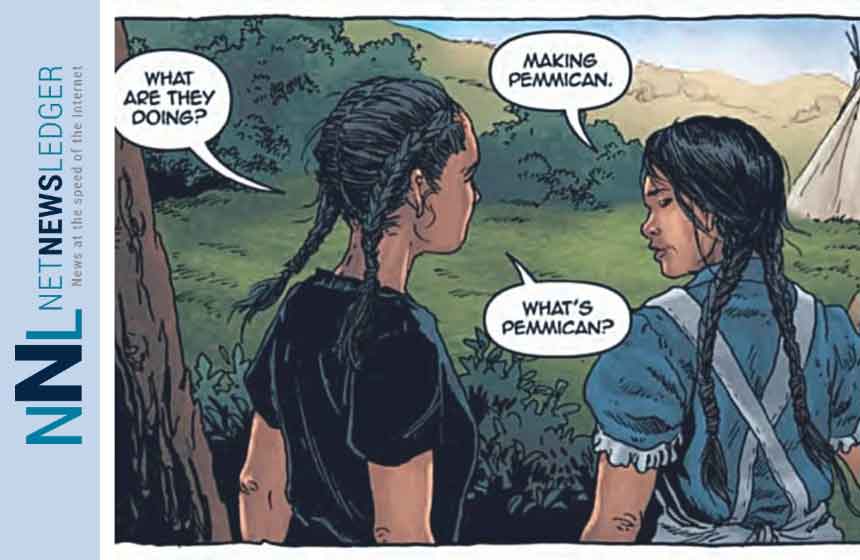

Among award-winning Winnipeg writers, Katherena Vermette’s second graphic novel in her series A Girl Called Echo: Red River Resistance was released in the fall. It tells the story of a modern young Métis woman who travels back in time to the summer of 1869.

Local Cree teacher Tasha Spillett recently published Surviving the City, a story of two young Indigenous women grappling with the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls. The graphic novel was on the best-seller lists at McNally Robinson for the final months of 2018.

One of the most interesting things about graphic novels is their ability to involve Indigenous and non-Indigenous artistic collaboration. Local Anishinaabe writer Jennifer Storm, for example, created the graphic novel Fire Starters about her community of Couchiching First Nation with non-Indigenous artist Scott Henderson.

Graphic novels, as in the past, encompass stories of Indigenous experience while also embodying modern ideas and activities such as reconciliation and treaties.

Indigenous graphic narratives are innovations on ancient storytelling traditions, using combinations of image and word to record and perform Indigenous expressions, histories, and art. They are found on rock, earth, and skin, the libraries of North America.

And now comic books, too.

Niigaan Sinclair

Niigaan Sinclair

Originally appeared in the Winnipeg Free Press on February 12, 2019. Republished with the permission of the author