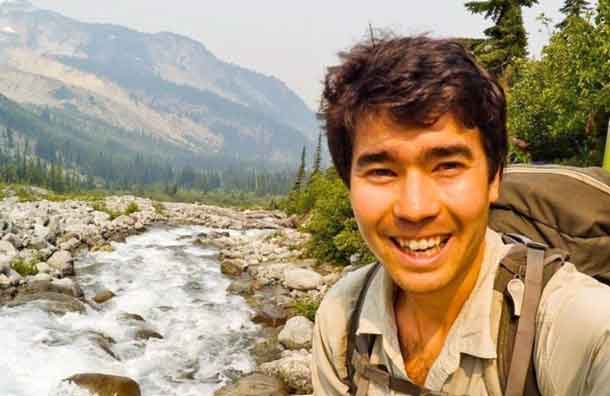

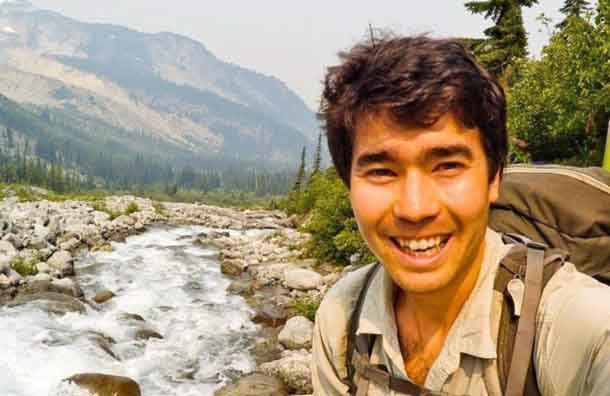

Missionary John Allen Chau is believed to have been killed after trying to convert a tribe on a remote Indian island to Christianity

By Rina Chandran

BANGKOK – (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – The suspected killing of an American missionary on a remote Indian island has sparked calls to better protect indigenous people from increasing pressure to free up their land for tourism, mines and highways.

John Allen Chau, 26, is believed to have been killed last week after travelling to North Sentinel – part of the archipelago of Andaman and Nicobar, in the Bay of Bengal – to try to convert the tribe to Christianity.

The Sentinelese are generally considered the last pre-Neolithic tribe in the world, and the Indian government has for years protected them by declaring the island off-limits to visitors.

But earlier this year, the government issued a notification exempting foreign nationals from needing special permits to visit more than two dozen islands, including North Sentinel and others inhabited by indigenous people.

Conservationists say the easing of restrictions could signal that these islands may be opened up for tourism, which would be damaging for the aboriginal people.

“A wealth of indigenous knowledge has already been lost because of intrusions, and trying to integrate them into our way of life, and the loss of traditional habitats,” said Manish Chandi, a senior researcher at Andaman Nicobar Environment Team.

“We need stricter enforcement of our laws for them to be truly effective,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The aboriginal people of Andaman and Nicobar are protected by a 1956 law that designates the areas where they have lived as tribal reserves, with little access for outsiders.

Yet the law is often flouted by tourists, poachers and others, with few held to account, Chandi said.

Elsewhere in the country, indigenous people are increasingly being forced off their land to make way for dams, mines and wildlife parks, rights groups say.

More than half India’s 104 million tribal people live outside their traditional habitats, with many also moving for jobs and educational opportunities, according to the tribal affairs ministry.

Indigenous people make up less than 10 percent of India’s population, yet account for 40 percent of people uprooted from their homes between 1951 and 1990, according to the New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research.

Only a quarter of them have been resettled elsewhere.

The land rights of indigenous people in so-called “scheduled areas” with a tribal majority are protected by the Constitution, yet they are among the “most vulnerable, most impoverished” groups, said Namita Wahi, a fellow at CPR.

“Despite the centrality of land to the identity, economy, and culture of tribal people, they have disproportionately borne the burden of economic development,” she said.

Constitutional protections are “fragmented and contradictory”, giving the state the right to acquire tribal land for its own purposes, she said.

Tribal areas are typically resource-rich, making the land attractive, while a draft National Forest Policy could further marginalize them by allowing private firms to grow and harvest commercial plantations.

The stakes for the Sentinelese in the Andaman are even higher, said Stephen Corry, director, Survival International.

“All uncontacted tribal peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected. We have to do everything we can to secure it for them,” he said.

(Reporting by Rina Chandran @rinachandran; Editing by Jared Ferrie. Credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation