THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Julia Smith, Simon Fraser University; Benjamin Hawkins, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Jappe Eckhardt, University of York, and Ross MacKenzie, Macquarie University

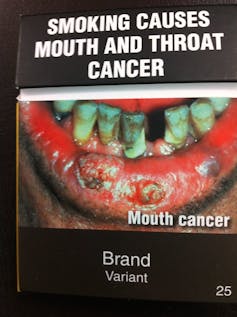

No matter how you look at it, a standardized cigarette pack is ugly. The colours are unappealing, the font bland and the large graphic health warnings gruesome. That’s why standardized packaging is such an effective public health policy — and why tobacco companies hate it.

The Canadian government is currently drafting regulations on standardized tobacco packaging as required by the new Tobacco and Vaping Products Act passed in May 2018. Tobacco companies are trying to weaken the regulations through lobbying and public relations campaigns.

Our research finds that these efforts are based on the same arguments and selective sources of information that the industry has used in other countries that have proposed similar measures, including Australia, the U.K. and the Netherlands.

Read more:

Australia’s plain tobacco packaging law at the WTO

We reviewed tobacco industry campaigns from around the world and found they all used the same key messages: That no evidence exists to support claims for the effectiveness of plain packaging; that such legislation contributes to a “slippery slope” of regulation that would accelerate the encroachment of the “nanny state” into citizens’ lives; that standardized packaging represents a threat to intellectual property rights and would increase the illicit trade in tobacco products.

To support these messages, public relations documents refer exclusively to studies funded by the tobacco industry or from groups with links to the tobacco industry.

Misleading messages

In Canada, JTI-MacDonald, the country’s third-largest tobacco company, launched the Both Sides of the Argument campaign, which claims to presents the “facts” against standardized packaging using websites, posters, advertisements, as well as Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Campaign materials argue that no credible evidence has emerged from Australia to support the effectiveness of standardized packaging, and repeat the same misleading messages used to challenge legislation in Australia and the U.K.

The campaign quotes research from consulting firms paid for by tobacco companies, which do not describe their methods in detail or subject them to peer review.

Knowing they have little public credibility, tobacco companies rely on “arms-length” advocacy groups to create false controversy around packaging regulations.

For instance, the National Coalition Against Contraband Tobacco argues that “plain packaging has increased contraband tobacco in other countries and will likely do the same in Canada” without providing evidence of increased illicit activity elsewhere.

The coalition receives funding from the tobacco industry and lists the Tobacco Manufactures Association as one of its members.

The Canadian Convenience Store Association, which has also received tobacco industry funding, argues that plain packaging would hurt small business, basing its claim on “detailed studies from Australia,” which were commissioned by British American Tobacco Australia and Philip Morris Australia.

What is presented as concern for the unfair treatment of small, local businesses is in fact the desire of some of the largest and most profitable global corporations to protect their profits at the expense of public health.

Diversionary tactics

A recent poll by Global News found that 63 per cent of respondents in Canada did not think standardized packaging would reduce smoking rates. This not only suggests that tobacco industry public relations campaigns are working, they’re also muddying the debate by framing success of the policy in terms of immediate smoking reductions.

This is a diversionary tactic also used in Australia, with some success, and it is now being reproduced in Canada.

Proponents of standardized packaging do not claim the policy will result in immediate smoking reductions. The long-term goals are to discourage people (especially youth) from taking up smoking, to encourage smokers to quit and to avoid relapse among ex-smokers. Evidence from Australia demonstrates that standardized packaging is making progress in achieving these goals.

Canadian policymakers can anticipate ongoing opposition from tobacco companies when they enact packaging legislation. Experiences from Australia and elsewhere suggest that industry campaigns do not end with implementation, but continue on after new laws are introduced in an attempt to discredit and ultimately repeal the policy.

(AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Policy advocates must therefore remain vigilant and prepared to counter industry misinformation.

Adopting standardized packaging policy is not only crucial to protect the health of Canadians, but will have international significance.

In implementing the regulations, Canada stands with those countries that have introduced similar legislation (France, the U.K., Norway, New Zealand, Ireland, Hungary, Slovenia and Belgium) and acts as a model to those countries considering the policy. As this policy spreads, momentum will build, including in low- and middle-income countries that may have less established tobacco control policies in place.

Through standardized packaging measures, Canada can not only secure the health of its citizens and future generations, it will reinforce its role as a global leader in tobacco control and public health.![]()

Julia Smith, Research Associate, Simon Fraser University; Benjamin Hawkins, Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Jappe Eckhardt, Lecturer in Politics and International Relations, University of York, and Ross MacKenzie, Lecturer in Health Studies, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.