Urban vegetation has implications for human mental and physical health, and combats flooding, heat, pollution and soil erosion

Can the Russians teach us anything about improving the quality of life in a major industrial city?

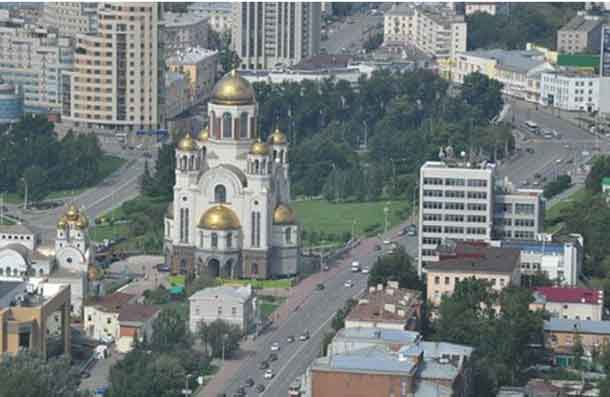

The authors of a new five-part series of articles believe so, especially from the ‘green city’ project being implemented in Russia’s fourth-largest city, Ekaterinburg (named after Peter the Great’s wife) on the Ural mountains.

This is Part 1 of the series, to be published on Mondays.

By Natalia Pryadilina,

Roy Damary

and Allan Bonner

Many of the world’s great cities are known for their topography. San Francisco’s hills, Sydney’s harbour, the canals of Venice and Amsterdam come to mind.

So does greenery. The huge parks of New York and London, Toronto’s ravines, and the palm trees of Los Angeles all make these cities unique.

Yet urban vegetation is more than a tourist attraction. It has implications for human mental and physical health, and is part of the solution to flooding, heat, pollution and soil erosion.

We’ve been studying Ekaterinburg, a large industrial city in Russia that has taken on a project to green itself. All cities can learn from the Ekaterinburg experience.

With its population of almost 1.5 million, Ekaterinburg is the fourth largest Russian city (after the mega-cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, and just behind similarly-sized Novosibirsk). It’s a major industrial and mining centre, and transport hub for the Trans-Siberian Railway. Its claims to history include the place where the Bolsheviks executed the tsar and his family, and where Boris Yeltsin was regional governor before his decisive intervention at the end of the U.S.S.R.

The city sits abreast the Ural Mountains at 245 metres above sea level, straddling Europe and Asia. It’s at much the same latitude as Aberdeen, Scotland, or Copenhagen, Denmark, but with much more extreme temperatures.

There are about 20 square metres of green spaces for common use per resident. These include open spaces like parks, squares and boulevards. In addition, there are about 111 square metres of forest parks and urban woodland per person.

Both these ratios are inadequate. To put these ratios into perspective, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), each urban dweller is supposed to require no less than 50 square metres of urban green spaces and 300 square metres of suburban forests.

WHO has conducted much research on “Healthy Cities.” The organization has issued a checklist, which, beyond the obvious health and safety concerns, includes:

- a sustainable eco-system (WHO explains how to measure sustainability);

- citizen participation in improving the health of cities;

- access to resources (i.e. the green spaces and forests).

Ekaterinburg is well behind in claiming healthy city status compared with the world leaders of Hong Kong, Tokyo, Copenhagen, Stockholm and Sydney. Part of the problem is the high number of vehicles. As in many European cities, Ekaterinburg has its trams, modern buses and even a metro, but still cars and trucks pollute the air.

Part of the solution is vegetation. The city government has therefore begun a major project to green the city. It has the support of the city council and the administration of the Sverdlovsk Region in which Ekaterinburg is located. And it involves a number of specialists and environmentalists.

Goals will be met primarily by expanding and maintaining green space and using the cleansing properties of trees. Trees – often called the lungs of the planet – have the indispensable ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and replace it with oxygen (the process of photosynthesis about which we all learned in school biology class). In a day, a medium-sized tree releases about two litres of oxygen. This is enough to provide human breathing needs for three days. Looked at another way, each hectare of forest during the day absorbs on average 150 to 170 litres of carbon dioxide and produces 180 to 200 litres of oxygen by photosynthesis. That’s enough oxygen for 200 people.

Another characteristic of trees is less well known: the leaves of many trees release into the air special substances – phytoncides – that kill illness-producing bacteria. Indeed, most trees give off these volatile, biologically active organic substances. Sometimes these substances form a haze. Phytoncides can destroy pathogenic microbes and fungi, exert a strong influence on multicellular organisms and even kill insects.

Phytoncides were discovered in 1928 and their name coined by Russian biochemist Boris P. Tokin.

The best producer of therapeutic volatile organic substances is the pine forest. In pine and cedar forests, the air is practically sterile. Pine phytoncides increase the general constitution of a person, and have a beneficial effect on the central and sympathetic nervous system. Also, such trees as cypress, maple, viburnum, magnolia, jasmine, white acacia, birch, alder, poplar and willow display bactericidal properties.

Phytoncides play an important role in plant immunity and in the interrelationships of organisms in bio-geosciences (the ecosystem of the entire world characterized by multiple interacting and interlocking biological and physical processes. These govern local to global cycles of carbon, nitrogen, water and energy.

Russia certainly has forests. In fact, its boreal taiga, along with Canadian and Alaskan forests, stretch around the globe. These forests are huge resources for their countries and the world as a whole. Nevertheless, population density and pollution mean cities need trees within the city, not just greenbelts around them. This means parks, trails and city woodland.

What kind of trees? Pine, larch, spruce, silver birch, poplar, ash, tatar and ginnala maple, wych-elm, apple trees and maak cherry trees. To them may be added lilac, hawthorn and linden, which has a place in any Russian environment, especially in urban woodland and parks. Most of these species are quite resistant to atmospheric pollution, although ash, linden and spruce are intolerant of dust.

The choice of trees for an urban environment in Russia is great. In a sense, planting trees is the easy part of greening a city.

Part 2 next Monday: The importance of green spaces.

Dr. Allan Bonner is a Troy Media columnist who is an urban planner and crisis manager. His next book is Cyber City Safe: Emergency Planning Beyond the Maginot Line. Dr. Roy Damary, Oxonian, Harvardian and graduate of Lausanne University, is president of the Swiss-based Graduate Institute of Business and Management and honourary professor of the Ural State Forest Engineering University in Ekaterinburg, Russia. He teaches online business courses at Robert Kennedy College, Zurich. Natalia Pryadilina is associate professor of the Department of Economics and Economic Security of the Ural State Forestry Engineering University (USFEU, Ekaterinburg). Her main scientific interests are strategies for development of regions and enterprises, and forest management. The results of the research work have been published in more than 50 scientific articles.

© Troy Media

The views, opinions, and positions expressed by all columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of NetNewsLedger.