By Costas Pitas and Kylie MacLellan

LONDON (Reuters) – Prime Minister Theresa May was fighting to hold on to her job on Friday as British voters dealt her a punishing blow, denying her the stronger mandate she had sought to conduct Brexit talks and instead weakening her party’s grip on power.

With no clear winner emerging from Thursday’s parliamentary election, a wounded May signalled she would fight on, despite losing her majority in the House of Commons. Her Labour rival Jeremy Corbyn said she should step down.

With 643 out of 650 seats declared, the Conservatives had won 313 seats and were therefore no longer able to reach the 326-mark they would need to command a parliamentary majority. Labour had won 260 seats.

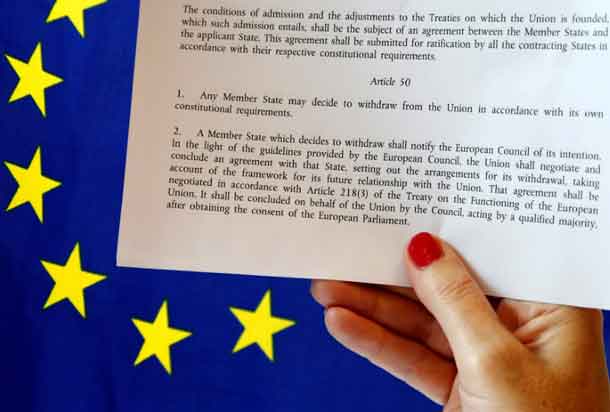

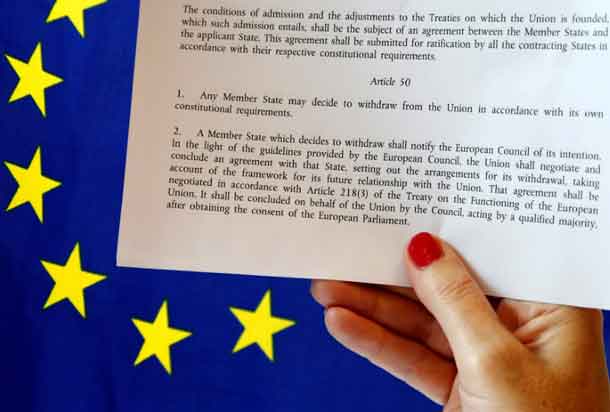

With talks of unprecedented complexity on Britain’s departure from the European Union due to start in just 10 days’ time, it was unclear who would form the next government and what the fundamental direction of Brexit would be.

“At this time, more than anything else this country needs a period of stability,” a grim-faced May said after winning her own parliamentary seat of Maidenhead, near London.

“If … the Conservative Party has won the most seats and probably the most votes then it will be incumbent on us to ensure that we have that period of stability and that is exactly what we will do.”

After winning his own seat in north London, Corbyn said May’s attempt to win a bigger mandate had backfired.

“The mandate she’s got is lost Conservative seats, lost votes, lost support and lost confidence,” he said.

“I would have thought that’s enough to go, actually, and make way for a government that will be truly representative of all of the people of this country.”

From the EU’s perspective, the upset in London meant a possible delay in the start of the talks and an increased risk that negotiations would fail.

“We need a government that can act,” EU Budget Commissioner Guenther Oettinger told German broadcaster Deutschlandfunk. “With a weak negotiating partner, there’s a danger that the negotiations will turn out badly for both sides.”

Conservative member of parliament Anna Soubry was the first in the party to disavow May in public, calling on the prime minister to “consider her position”.

“I’m afraid we ran a pretty dreadful campaign,” Soubry said.

May had unexpectedly called the snap election seven weeks ago, even though no vote was due until 2020. At that point, polls predicted she would massively increase the slim majority she had inherited from predecessor David Cameron.

Instead, she risks an ignominious exit after just 11 months at Number 10 Downing Street, which would be the shortest tenure of any prime minister for almost a century.

“MAY IS TOAST”

“Whatever happens, Theresa May is toast,” said Nigel Farage, former leader of the anti-EU party UKIP.

Sterling fell by more than two cents against the U.S. dollar, hitting an eight-week low of $1.2690, but by 0609 GMT it had recovered to $1.2721.

“A hung parliament is the worst outcome from a markets perspective as it creates another layer of uncertainty ahead of the Brexit negotiations and chips away at what is already a short timeline to secure a deal for Britain,” said Craig Erlam, an analyst with brokerage Oanda in London.

May had spent the campaign denouncing Corbyn as the weak leader of a spendthrift party that would crash Britain’s economy and flounder in Brexit talks, while she would provide “strong and stable leadership” to clinch a good deal for Britain.

But her campaign unravelled after a major policy u-turn on care for the elderly, while Corbyn’s old-school socialist platform and more impassioned campaigning style won wider support than anyone had foreseen.

In the late stages of the campaign, Britain was hit by two Islamist militant attacks in less than two weeks that killed 30 people in Manchester and London, temporarily shifting the focus onto security issues.

That did not help May, who in her previous role as interior minister for six years had overseen cuts in the number of police officers. She sought to deflect pressure on Corbyn, arguing that he had a weak record on security matters, but that did not stop questions about her own ministerial decisions.

With the smaller parties more closely aligned with Labour than with the Conservatives, the prospect of Corbyn becoming prime minister no longer seems fanciful.

That would make the course of Brexit even harder to predict. During his three decades on Labour’s leftist fringe, Corbyn consistently opposed European integration and denounced the EU as a corporate, capitalist body.

As party leader, Corbyn unenthusiastically campaigned for Britain to remain in the bloc, but has said that Labour would deliver Brexit if in power, albeit with very different priorities from those stated by May.

“What tonight is about is the rejection of Theresa May’s version of extreme Brexit,” said Keir Starmer, Labour’s policy chief on Brexit, saying his party wanted to retain the benefits of the European single market and customs union.

POTENTIAL ALLIANCES

On a nerve-racking night for the Conservatives, interior minister Amber Rudd held on to her seat by a whisker, while several junior ministers were swept away. In one of many striking moments, the party lost the seat of Canterbury for the first time in a century.

The Conservatives could potentially turn for support to Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), a natural ally, projected to win 10 seats.

But Labour had potential allies too, not least the Scottish National Party (SNP) who suffered major setbacks but still won a majority of Scottish seats.

The pro-EU, centre-left Liberal Democrats were having a mixed night. Their former leader, Nick Clegg, who was deputy prime minister from 2010 to 2015, lost his seat. But former business minister Vince Cable won his back, and party leader Tim Farron held on.

In domestic policy, Labour proposes raising taxes for the richest 5 percent of Britons, scrapping university tuition fees, investing 250 billion pounds ($315 billion) in infrastructure plans and re-nationalising the railways and postal service.

Analysis suggested that Labour had benefited from a strong turnout among young voters. UKIP saw a collapse in its support, shedding votes evenly to the two major parties instead of overwhelmingly to the Conservatives, as pundits had expected.

“UKIP voters wanted Brexit but they also want change,” Farage said.

“They are fundamentally anti-establishment in their attitudes and the vicar’s daughter (May) is very pro-establishment. And I think she came across in the campaign as not only as wooden and robotic but actually pretty insincere.”

In Scotland, the pro-independence SNP were in retreat despite winning most seats. Having won all but three of Scotland’s 59 seats in the British parliament in 2015, their share of the vote fell sharply and they lost seats to the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

The campaign had played out differently in Scotland than elsewhere, the main faultline being the SNP’s drive for a second referendum on independence from Britain, having lost a previous plebiscite in 2014.

SNP leader and First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said it had been a disappointing night for her party, while Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson said Sturgeon should take the prospect of a new independence referendum off the table.

(Additional reporting by Guy Faulconbridge, Alistair Smout, David Milliken, Paul Sandle, William Schomberg, Andy Bruce, William James, Michael Urquhart and Paddy Graham in London, Padraic Halpin in Dublin; Writing by Estelle Shirbon; Editing by Mark Trevelyan and Mark John)