THUNDER BAY – Anishinaabe – The following is an open letter that was sent to the Dean of the Bora Laskin Faculty of Law, and the Chair of Truth and Reconciliation, Lakehead University, on November 10, 2016:

Boozhoo,

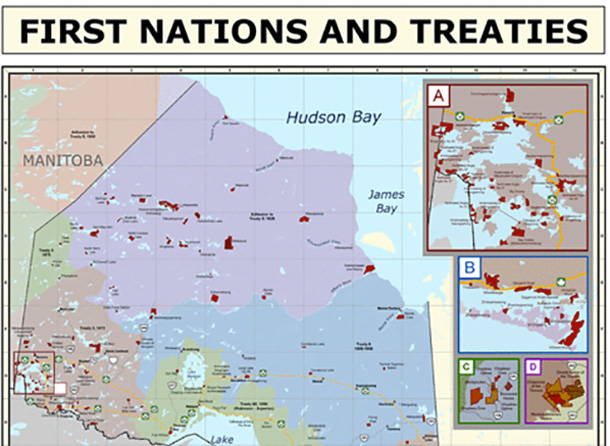

Once upon a time, explorers showed up in Anishinaabe aki and claimed it as their own. This was just part of how things were done then – if one group of explorers found Indigenous lands before another group, they assumed ownership to that land and named it. This method could be said to be the early beginnings of how Canada became a country. For Anishinaabeg, however, such naming and claiming is part of a larger process of ignoring Anishinaabeg peoples’ inherent relationship and responsibilities with the lands, waters, and beings we’ve lived with for thousands of years. Today, the Robinson-Superior Treaty and Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 and Treaty 3 (1873) may be utilized to push back on unilateral claiming. These treaties remain expressions of Anishinaabe territorial sovereignty today.

Fast forward a few hundred years, and the issue of naming as claiming remains in effect. But things are more complicated now; generations of identity regulation by the federal government have produced divisions between Indigenous peoples, awarding recognition to some and none to others. This politics of federal recognition is one way in which Canada lays claims to land: recognizing the territorial claims of those who find their self-governance authority within what the settler state will allow is much safer than recognizing the sovereignty of Indigenous nations that exist outside its purview. It is with this history in mind that we as Anishinaabeg and Indigenous scholars wish to discuss a recent claim to Anishinaabe territory.

In October 2016, Lakehead University posted to its website an employment opportunity for professorship in its Bora Laskin Faculty of Law. In part, that posting read: “Given the Faculty’s presence in Anishinaabe and Métis territory, preference will be given to qualified candidates with research and teaching expertise in either Anishinaabe law or Métis law or both.” While we are excited to see the establishment of a law program in Anishinaabe aki that centres Indigenous legal systems, as Anishinaabe citizens and scholars we aren’t sure how to interpret Lakehead’s claim that Thunder Bay, Ontario and surrounding areas are Anishinaabe and Métis territory. In truth, we were somewhat surprised. Within our respective families, communities, and research, we had not come across such a claim until now. We would therefore like to discuss this claim openly.

Before we share our thoughts, we want to acknowledge and recognize that Métis have and continue to experience colonial violence from Canadians and other Indigenous nations alike. In addition to land theft in the West and other forms of violence, this has also taken the form of questioning the very existence of Métis. We do not want to perpetuate such violence. We also want to be transparent that we have professional, personal and familial relationships with Métis individuals and families that we wish to uphold.

We also recognize that Métis identity is currently being debated by Métis themselves. Such debates put definitions of “Métis-as-mixed” in contrast with Métis as political peoplehood. While many Métis live within many different treaty areas including within Robinson Treaty lands and in Treaty 3 territory, we recognize the Métis as Indigenous peoples who came to define themselves as Métis through the establishment of a unique political consciousness in the Red River area and points west. Conversely, we agree with Métis scholars who argue that framing Métis as “mixed” effects all Indigenous nations in Canada because such approaches centre biological essentialism at the expense of the political consciousness and sovereignty that underwrites Indigenous peoples as nations.

These issues take on further complexity in northwestern Ontario for a number of reasons. One, the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) is engaging in agreements with natural resource corporations. Two, historically, many Anishinaabeg were misrecognized as “halfbreeds” by the Crown and its representatives. We understand that these MNO agreements with the settler government are being addressed by other Anishinaabeg and Métis so we will not address this here. Regarding misrecognition, this was a gendered and racialized approach to defining identity by prioritizing biological mixedness above Anishinaabe citizenship orders. For example, the Métis Nation of Ontario’s website states, “Prior to Canada’s crystallization as a nation, a new Aboriginal people emerged out of the relations of Indian women and European men.” We’d like to draw attention to how this implies Anishinaabe women were reimagined as being responsible for creating a new nation at the expense of their Anishinaabe citizenship, a reworking that both legitimizes Métis-as-mixed nationhood claims while removing women from being Anishinaabeg. Such constructions of Métis nationhood create complexities in understanding historical northern Ontario politics: we are aware that, in the lead up to the signing of the Robinson Treaties of 1850, some halfbreeds at Sault Ste. Marie claimed a separateness from Anishinaabeg and the nascent settler societies that would become Canada. We are also aware of the Halfbreed Adhesion to Treaty 3 (in 1874). Yet we would like to draw attention to how many “halfbreeds” were considered Anishinaabe through matrilineal Anishinaabe kinship and clan systems despite having some European ancestry. Indeed the issue of their “white blood” was not problematic until treaty negotiations when settler colonial governments needed to categorize and quantify “her Majesty’s Indians.” In fact, among Anishinaabeg, often halfbreeds were distinguished from Métis through different identifiers like “Red River Indians.” This is not to say that said halfbreed communities were not Indigenous, nor is it to say Métis did not travel back and forth from the Red River to these locales while using kinship governance to do so. However, we concur with Métis scholars when they suggest that said communities may or may not have thought of themselves in ways separate from the Métis of the west. Clearly, working through northern Ontario history requires great care in order to avoid reproducing settler colonial constructions of Indigeneity. Though committed to this ethic, we nonetheless struggle to do it right.

Getting back to the job ad, we are concerned that the phrase “Anishinaabe and Métis territory” rhetorically and powerfully names and claims Anishinaabe territory as Métis territory. First, we worry that the claim of Métis territory is a false claim. Halfbreeds were no doubt present at Fort William since the 19th century, but so were settler colonialists that sought to eliminate Anishinaabe presence through gendered and racialized misrecognition. Without a clear definition of what is “Métis territory” in this ad, we worry Lakehead may be reproducing a Métis-as-mixed-based claim to territoriality.

Further, in response to several emails inquiring into the meaning of this claim of “Métis territory,” on November 8, 2016 Dean Angelique EagleWoman responded. She suggested the Métis Nation of Ontario be contacted to gain an understanding of Métis presence in the Thunder Bay area. We were also made aware of the LU Faculty of Law’s 2013 protocol agreement, signed in part by the Métis Nation of Ontario as well as the Anishinabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians), Grand Council Treaty #3, and the Nishnawbe Aski Nation. Unfortunately, this response does not provide any clarification to the query into the meaning of “Métis territory.” First, the job advertisement claims territory, not presence. Second, ensconcing the relationship between the Bora Laskin Faculty of Law and the MNO in the internal architecture of “Advisory Committees” and “Protocol Agreements” also fails to elucidate the meanings of “Métis territory” that are being claimed in this job ad. The long silence between the emails sent and the response, paired with an opaque response that was eventually given on November 8th, which essentially sends Anishinaabeg down a garden path, is disappointing. In an era of Truth and Reconciliation, this way of responding to Anishinaabeg is also curious. Given the outcome of these initial exchanges, we pursue another angle. Here, we wish to attend to Métis agency–or rather, MNO agency–in advancing their interests in Anishinaabe homeland, lands, and territory. We also prompt Lakehead to reflect on its agency and interests in supporting the trajectory being taken by this organization on behalf of Métis.

Following this trajectory that queries Métis agency, we worry that this naming upholds a politics of recognition whereby Anishinaabe lands and waters are claimed by Métis and organizations without the express sanction of Anishinaabeg themselves. As we see it, recognition from Canadian law and jurisprudence is not enough to claim Métis title within Anishinaabe territory. Rather, we feel that if Métis want to claim land within Anishinaabe territory, and use settler institutions to advance their agenda, they would need to first have those conversations and agreements with Anishinaabeg. This would occur outside of Canadian law and Canadian institutions. We are unaware of any such serious and important conversations being had to date.

In thinking about Lakehead’s claim that it sits on Anishinaabe and Métis territory, we have come to see other potential dangers emerging more broadly within Canada. We see potential for the state to push its brand of “reconciliation” through universities, sometimes using Indigenous individuals to do so, to undermine Indigenous nationhood. Lakehead’s claim to sit within Anishinaabe and Métis territory acts as a microcosm in which we can see how the state uses its power to recognize forms of Indigenous nationhood that are amenable to its distorted version of sovereignty, namely “self-government.” Through recognizing self-government of Indigenous nations where such recognition is based on Canadian liberal multiculturalist approaches to Indigeneity–as opposed to decolonization–the state can work to hijack nationhood claims. Drawing on the Lakehead claim as an example, through recognizing Métis claims to Anishinaabe territory, the state and individuals within the university advancing its agenda, can erase Anishinaabe territorial sovereignty under a narrative of Canadian aboriginal and multicultural politics. In doing so, Canadian multiculturalism is positioned as timeless and universal. Anishinaabe sovereignty is eroded in this scenario.

For this reason, we wish to centre Indigenous political and legal orders in territorial claims as well as in relationships between Indigenous peoples and the state, and amongst Indigenous nations. It is not enough to rely on recognition from the Canadian state to make claims to another peoples’ territory. To be just in a decolonizing sense, claiming territory must be done through Indigenous nation-to-Indigenous nation relationships and agreements. The creation and use of wampum belts to document and practice relationships between Indigenous Nations is just one example. Particular to our situation, we have a responsibility to centre Anishinaabe law within all Anishinaabe territory. We therefore have a responsibility to centre Anishinaabe law within Métis-Anishinaabe territory claims, and this must trump any claims made through Métis-Canada/Ontario relationships. Moreover, in centring Anishinaabe law within a decolonizing context, we have a responsibility to centre the experiences, knowledges and voices or Nokomisag (grandmothers), Anishinabekwewag (women), and two-spirited peoples.

In closing, we would request Lakehead University change its job ad with the above points in mind, and, accordingly, review any other of its statements where Anishinaabe territory is discussed. Perhaps, as an example, the job ad could be rephrased to state “….situated in Anishinaabeg territory, specifically within Treaty 3, the Robinson-Superior Treaty area, and the Williams Treaty area of the Anishinaabeg and Canada. Through kinship with Anishinaabeg, this territory is also home to many Métis.” We also request discussion with Lakehead University and other universities located within Anishinaabe territories about moving forward in constructing shared understandings about where we live, work, play, and learn. Finally, we urge our Anishinabe relatives–our grassroots leaders in our communities and our leaders through traditional government and political/territorial organization–take notice of what has taken place, and voice any of your concerns or ideas in regards to how territory is claimed in instances such as this.

minaademowin,

Makwa dodem

Waaseyaa’sin Christine Sy

Lac Seul First Nation member

Ph.D Candidate, Indigenous Studies (Trent University)

Lecturer, Gender Studies (University of Victoria)

giizismoon@hotmail.com

Waase dodem

Damien Lee – Zoongde

Fort William First Nation citizen

Ph.D Candidate, Native Studies (University of Manitoba)

Assistant Professor, Indigenous Studies (University of Saskatchewan)

connectwithdamien@gmail.com

Makwa nin dodem

Anang Onimiwin nnindishnikaz gaye Dr. Celeste Pedri-Spade, PhD (University of Victoria)

Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation member

Assistant Professor, School of Northern and Community Studies (Laurentian University)

cvpedri@gmail.com

Helen Pelletier

Fort William First Nation member

hdpellet@lakeheadu.ca

Tannis Kastern

Fort William First Nation member

Lakehead University Student Union

Director & Member of Lakehead University Native Student Association/National Aboriginal Caucus (CFS)

Stephanie MacLaurin

Fort William First Nation

Master of Arts Candidate, Indigenous Governance (University of Victoria)

smaclaur@lakeheadu.ca

Ph.D Student, Queens University