TORONTO – The opioid epidemic is the greatest drug safety crisis of our time. Addressing it involves facing unpleasant truths and asking difficult questions.

TORONTO – The opioid epidemic is the greatest drug safety crisis of our time. Addressing it involves facing unpleasant truths and asking difficult questions.

I’ve lost track of how many times over the last year the epidemic has been front-page news – the death of Prince, naloxone, fentanyl, newborns in agonizing withdrawal and so on.

Despite the best of intentions, doctors flood homes with opioids purer and stronger than heroin, destroying countless lives in the process

This epidemic is distinguished by its catastrophic toll – hundreds of thousands dead, uncountable millions harmed – and the fact that, unlike SARS, Ebola or influenza, there is no end in sight. The reason is complicated but relates in part to prevalent beliefs about the role of these drugs in medical practice.

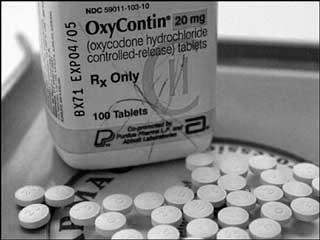

One unpleasant truth related to opioid abuse is that well-intentioned prescribing fueled this crisis. For 20 years, doctors have prescribed opioids – oxycodone, hydromorphone and others – liberally for chronic pain, one of the most common problems we see. We did this because relief of suffering is our primary goal, because we are conditioned to intervene, and because we were assured on some authority that it was safe, effective and based on sound medical evidence.

It’s not.

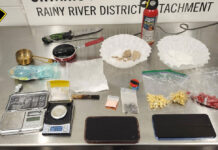

Despite the best of intentions, we flooded North American homes with opioids purer and often stronger than heroin. These drugs increasingly fell into the wrong hands, destroying young lives and countless families in the process.

But another unfortunate truth is that even when patients with chronic pain followed our instructions, we caused more harm than we anticipated. By some estimates, 10 per cent spiralled into addiction, even though we’d been told this would happen only rarely. Some crashed their cars. Others fell, fracturing bones or suffering head injuries. And some, especially those prescribed high doses or who took their medication with sedatives or alcohol, simply went to sleep and didn’t wake up.

And yet we continue. The reasons are more complicated: we’ve grown accustomed to it, writing a prescription is easy, pills are expected, they’re covered by insurance while other treatments aren’t, and so on. But a critical factor is that our patients often tell us opioids work, that they need them to function and that they couldn’t face life without them. These testimonies, delivered honestly and with conviction, are powerful.

To openly question the role of opioids in the treatment of chronic pain is to draw the ire of patients and, sometimes, the displeasure of colleagues, particularly those who specialize in pain medicine. But it is long past time that doctors (and patients) reflect on what happens when these drugs are prescribed for months or years at a time. And it is time to reflect on what the honest objectives of drug therapy should be.

Opioids do relieve pain, and can be valuable after a fracture or major operation. But that analgesia wanes with time, a circumstance known as tolerance. As pain resurfaces, doses are often increased and the cycle continues. An even more pernicious circumstance is physical dependence, which develops within days and results in withdrawal symptoms (pain, abdominal cramping, irritability and drug craving) when opioids are stopped. These symptoms abate when the drug is resumed. Is it any wonder that a patient with chronic pain would construe this as effectiveness? It’s a recipe for self-perpetuating therapy.

Doctors prescribe medications to afford benefits in excess of harms. Regardless of drug or patient, a benefit is never guaranteed and harms always loom. This is why we don’t prescribe antibiotics for the common cold. Yes, the risk is low, but there is no conceivable benefit because viruses don’t respond to antibiotics.

But what happens when the benefits of a drug decline with time, yet the harms persist or even increase? What if the benefits come to be defined by avoidance of withdrawal symptoms, including pain, thereby clouding the assessment of effectiveness? What if patients reject this concept, as they often emphatically do? And what if, unlike most other medicines, it isn’t possible to simply stop therapy without triggering a cascade of new and very serious problems?

These questions merit reflection by every physician who treats chronic pain and the patients who suffer from it.

The goal of pain medication isn’t simply pain relief; the goal is to help more than harm. Sometimes chronic opioid therapy meets this objective but it does so less often than we think.

David Juurlink is professor and head of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Toronto. He is also an expert advisor with EvidenceNetwork.ca. @davidjuurlink

© 2016 Distributed by Troy Media