LONDON (Reuters) – Britain’s finance minister said on Monday the country’s economy was strong enough to cope with volatility caused by its vote to leave the European Union, whose leaders demanded a quick divorce and promised no special treatment.

With financial markets shaken by the shock outcome of Thursday’s referendum, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said uncertainties over the global economy had heightened and called for a “united, stable EU, and a stable, prosperous Britain”.

But British politics are in crisis, with the ruling Conservatives facing a leadership battle and lawmakers in the main opposition party, Labour, trying to topple their leader.

On the financial markets, the pound has come under siege and the euro has been struggling since the referendum, in which 52 percent of voters backed a British exit from the EU, or Brexit.

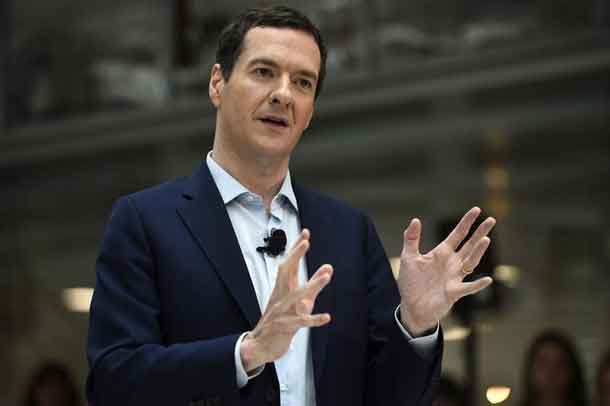

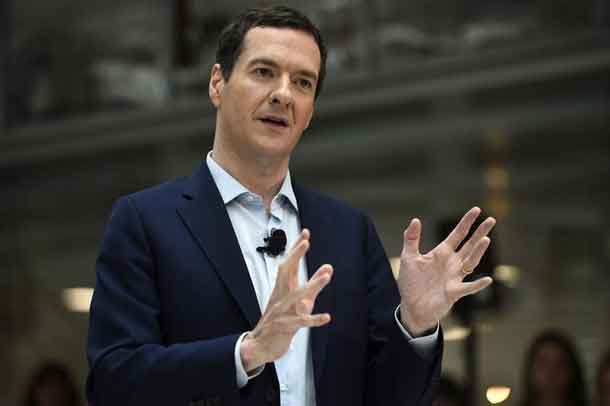

Speaking publicly for the first time since the vote, British Chancellor George Osborne said he was working closely with the Bank of England and officials in other leading economies for the sake of stability as Britain reshapes its relationship with the EU.

“Our economy is about as strong as it could be to confront the challenge our country now faces,” he told reporters at the Treasury. “It is inevitable after Thursday’s vote that Britain’s economy is going to have to adjust to the new situation we find ourselves in.”

Boris Johnson, a leading proponent of a Brexit and likely contender to replace Prime Minister David Cameron who resigned on Friday, praised Osborne for saying “some reassuring things to the markets.”

He said outside his home in north London that it was now clear “people’s pensions are safe, the pound is stable, markets are stable. I think that is all very good news.”

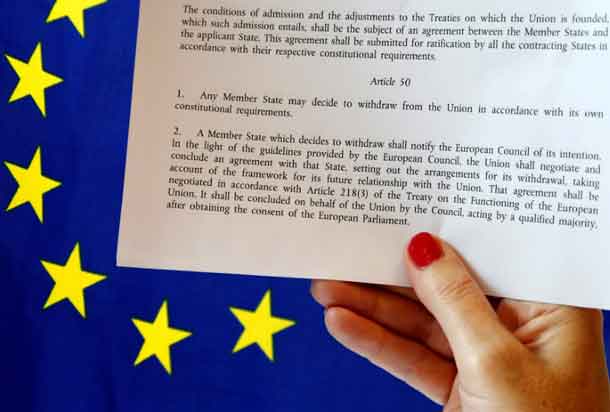

The vote last Thursday to leave the trading and political bloc Britain joined 43 years ago delivered the biggest blow since World War Two to the European project of forging greater unity.

Cameron, who is staying on for three months as a caretaker, refused to notify the EU formally of Britain’s intention to quit, leaving the job to whoever replaces him as Conservative leader and prime minister.

LONG LIMBO

The replacement is unlikely to be in office before October, so Britain and the EU are left in a political limbo.

Many European leaders want rapid action, and say there is no going back on the vote.

“France like Germany says Britain has voted for Brexit. It should be implemented quickly. We cannot remain in an uncertain and indefinite situation,” French finance minister Michel Sapin said on France 2 television.

Guenther Oettinger, a German member of the EU’s executive European Commission, also issued a warning.

“Every day of uncertainty prevents investors from putting their funds into Britain, and also other European markets,” he told Deutschlandfunk radio. “Cameron and his party will cause damage if they wait until October.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has taken a softer line. She says she will not battle now over the timeframe and has underlined the need to continue a positive trade relationship with Britain, a big market for German carmakers and other manufacturers.

But a Merkel ally, Volker Kauder, made clear the exit negotiations would not be easy. “There will be no special treatment, there will be no gifts,” Kauder, who leads Merkel’s conservatives in parliament, told ARD television.

BETTING ON THE STATUS QUO

Financial markets misjudged the referendum, betting on the status quo despite abundant signs that the vote would be close.

When reality dawned, the reaction was brutal. Sterling fell as much as 11 percent against the dollar on Friday for its worst day in modern history, while more than $2 trillion was wiped off the value of world stocks.

While the shock and panic appeared to have subsided on Monday, Asian and European stocks fell again, albeit by smaller amounts.

Sterling stayed under siege, holding above a 31-year low against the dollar, and dragged down the euro. As investors sought safety, the yield on British 10-year government debt fell below one percent for the first time.

Many economists have cut economic growth forecasts for Britain, with Goldman Sachs expecting a mild recession within a year.

But the risks affect economies far beyond Britain.

“Against the backdrop of globalisation, it’s impossible for each country to talk about its own development discarding the world economic environment,” Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told the World Economic Forum in the city of Tianjin.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe instructed his finance minister to watch currency markets “ever more closely” and take steps if necessary.

Abe has tried to engineer a weaker yen to encourage exports and help revive the Japanese economy. But after early success, investors have sought safety in the yen this year due to stock market turmoil and now the Brexit vote, pushing it back up.

At the weekend, the policy chief of Abe’s LDP party held open the possibility of currency intervention to weaken the yen and temper “speculative, violent moves”.

DIVIDED PARTIES

Johnson tried — in EU eyes — to square the circle on the vexed question of Britain’s trade relationship with the bloc after the divorce goes through.

“There will continue to be free trade, and access to the single market,” Johnson wrote in a regular column for the Daily Telegraph newspaper.

He did not set out any details of how the arrangement would work, but suggested Britain would not accept free movement of workers, saying the government could implement an immigration policy which suited the needs of business and industry.

Some politicians and economists have said Britain could follow the example of Norway, which remains outside the EU but has signed up to its single market, the world’s biggest.

However, single market rules stipulate that countries must accept the free movement of people as well as goods. Yielding on immigration would anger many Britons who voted to leave, believing this would halt a tide of workers from eastern Europe.

Johnson is expected to declare soon that he is running to lead the Conservatives, who have been divided for decades between pro- and anti-EU factions.

Divisions within the opposition are also deep. A wave of Labour lawmakers resigned from leader Jeremy Corbyn’s team on Monday, adding to the 11 senior figures who quit on Sunday.

They say Corbyn, a veteran left-winger who has strong support among ordinary party members, is not fit to lead the party and point to his low-key campaign to keep Britain in the EU.

If repeated at the next parliamentary election, due in 2020, they fear Labour faces disaster following its near wiping out in Scotland last year. Corbyn has said he is going nowhere.

By William James (Additional reporting by Kevin Yao, Costas Pitas, Bate Felix, Andrea Shalal, Minami Funakoshi and Tetsushi Kajimoto, Writing by David Stamp, Editing by Timothy Heritage)