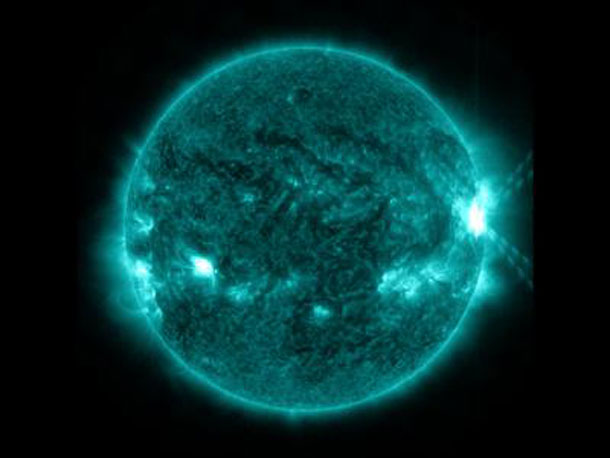

THUNDER BAY – A coronal mass ejection, or CME, surged off the side of the sun on May 9, 2014, and NASA’s newest solar observatory caught it in extraordinary detail. This was the first CME observed by the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph, or IRIS, which launched in June 2013 to peer into the lowest levels of the sun’s atmosphere with better resolution than ever before. Watch the movie to see how a curtain of solar material erupts outward at speeds of 1.5 million miles per hour.

IRIS must commit to pointing at certain areas of the sun at least a day in advance, so catching a CME in the act involves some educated guesses and a little bit of luck.

“We focus in on active regions to try to see a flare or a CME,” said Bart De Pontieu, the IRIS science lead at Lockheed Martin Solar & Astrophysics Laboratory in Palo Alto, California. “And then we wait and hope that we’ll catch something. This is the first clear CME for IRIS so the team is very excited.”

The IRIS imagery focuses in on material of 30,000 kelvins at the base, or foot points, of the CME. The line moving across the middle of the movie is the entrance slit for IRIS’s spectrograph, an instrument that can split light into its many wavelengths – a technique that ultimately allows scientists to measure temperature, velocity and density of the solar material behind the slit.

The field of view for this imagery is about five Earths wide and about seven-and-a-half Earths tall.

Lockheed Martin Solar & Astrophysics Laboratory designed the IRIS Observatory and manages the mission. NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, provides mission operations and ground data systems. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the Explorers Program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C.