But here’s why Harm Reduction is the best policy

EDMONTON – Health – Doctors treating addicts from Vancouver’s Downtown East Side have been asking the federal government to extend a trial program under which they were allowed to write prescriptions for diacetyl morphine. Health Minister Rona Ambrose has opposed extending the program. On March 25th, Providence Health Care took the doctors’ case before the B.C. Supreme Court.

Why is diacetyl morphine controversial? Because it’s better known by the trade name it had before it was made illegal: heroin.

Ambrose’s actions are of a piece with the Conservative government’s continuing opposition to harm reduction strategies in Canada. In October of 2013 it amended the special access program (which makes restricted drugs available for research purposes) to prevent clinicians from prescribing heroin, cocaine, and ecstasy. After being ordered to extend the operating permits of Vancouver’s Insite supervised injection facility by a unanimous Supreme Court of Canada decision (Canadav. PHS Community Services Society, 2011 SCC 44), the government wrote new legislation making it harder for similar facilities to be opened in the future. It has also increased the penalties for drug possession and trafficking.

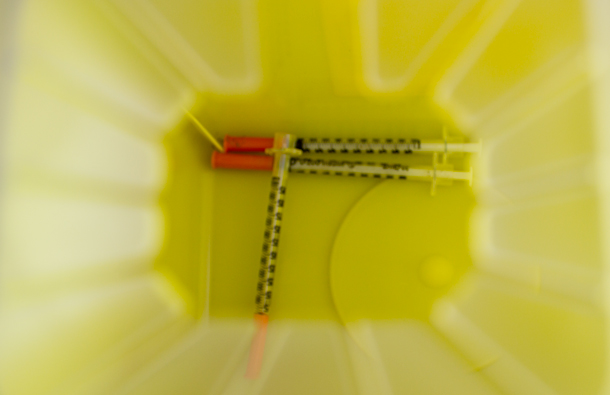

The doctors justify their request under the concept of Harm Reduction, an umbrella term for many public health policies that seek to minimize the harm suffered by recreational drug users. It embraces many programs like needle exchanges, safe injection sites, and offering free, anonymous HIV testing to at-risk populations. In this case, the doctors argue that putting addicts into regular touch with healthcare providers makes it easier for them to enter treatment and receive help for their other afflictions like homelessness and mental illness.

Opponents of harm reduction argue that these policies risk creating the impression that the activities in question can be made safe, attracting more people – who would otherwise be deterred – to partake in them. They are reasoning by analogy from the often observed fact that safety features in automobiles save lives, but lead to more accidents as drivers who feel protected take more risks.

I am uncertain whether this is the Conservative government’s stance on harm reduction – it has, here as in so many things, neglected to describe its reasoning for its policies. Rather than set up a straw man, an easy argument to knock down, I am trying (as I try in all my columns) to find the best arguments for a policy and present them strongly, even if they are not the arguments embraced by the policy’s supporters.

Both advocates and critics of Harm Reduction have respectable arguments in their favour. Both definitely favour reducing harm, but have opposed ideas of how to achieve it. One side argues for reducing the harms directly, while their opponent argues that such attempts will only increase the overall harm, for let’s not forget that every heroin addict has relatives and friends who are hurt by their addiction, and society should avoid creating more addicts wherever it can.

I have to side with the Harm Reduction advocates in this case. The harms predicted by their opponents are hypothetical. They seem to believe the public at large has a vast unsated desire to indulge in drugs which is deterred only by the threat of its illegality. This I find hard to credit. Ask yourself whether you or anyone you know is held back from experimenting with using intravenous drugs solely by its illegality and risk.

I also find it very hard to see how prescribing heroin to addicts and ensuring they practice safe injection techniques could be more harmful than the prohibition of narcotics has been.

The alternatives to doctor-prescribed heroin are evident every day in every major city: a massive and violent illegal drug trade, addicts stealing and prostituting themselves for their fixes, overdoses, poisonings due to cutting agents like , and soaring rates of Hepatitis C and HIV infections all of which contribute greatly to the cost of providing public services.

Arguably we, the citizens of Canada, are all being harmed by a prohibition- and punishment-centred approach to drug addiction. Changing our drug laws to something sensible is perhaps too much to ask in the near term – the least we can do is reduce the harm already being inflicted.

Michael Flood is a writer and creative director at Arrowseed, an Edmonton-based marketing firm. He holds an MA in Philosophy from the University of Alberta.

Read more Just Asking

Follow Just Asking via RSS