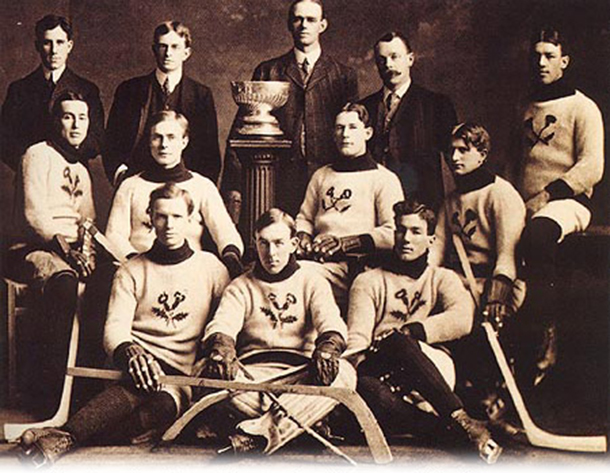

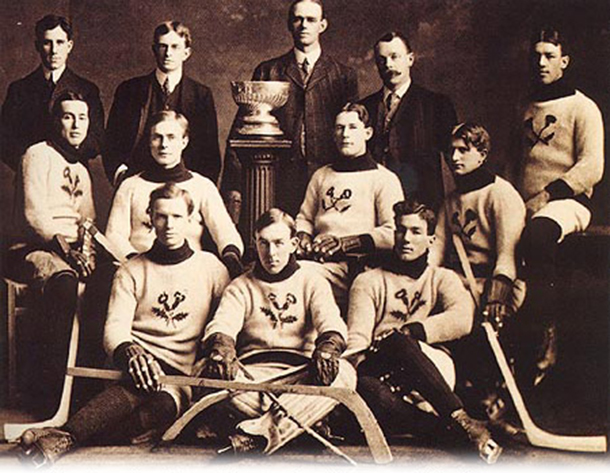

photograph. Back row: team president Lowry

Johnson, Russell Phillips, coach and trainer

J. A. Link, and team manager Red Hudson.

Middle row: Roxy Beaudro, Tom Hooper,

Tommy Phillips, Billy McGimsie, and Joe Hall.

Front row: Si Griffis, Eddie Giroux, and Art Ross.

THUNDER BAY – Sports – There are many stories about ice hockey. It is often said that a person would be hard pressed to find a Canadian without a link to the great game and thus, some story to tell. But now the sport and its passion are international, as are the tales.

Some of these stories are contained in the massive body of materials on ice hockey that exists. Roch Carrier’s The Hockey Sweater (1979), a children’s book about the life story of famous National Hockey League (NHL) professional player Maurice “The Rocket” Richard, is a classic. Also, there are the likes of many published stories such as the following: New York Rangers’ coach, Lester Patrick, at the age of 44, playing in goal in the 1928 NHL Stanley Cup finals after the regular goaltender, Lorne Chabot, got injured (the game ended in a 0 – 0 tie); NHL Boston Bruin tough guy, Eddie Shore, ending the career of the Toronto Maple Leaf’s Ace Bailey in 1933; Gordie Howe and his two sons playing on the same forward line for the Houston Aeros of the professional World Hockey Association (WHA) in 1973; the names of players and coaches misspelled on the Stanley Cup; and Canada’s Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, writing a hockey book. The list goes on and on.

Also, ice hockey is characterized by a multitude of leagues, trophies, and records. [Of interest, the Jack Adams trophy that is awarded annually to the NHL’s Coach of the Year is named after Jack Adams who was born in Thunder Bay (Fort William).]; there are as many things as imaginable, including births and deaths, and definitely lots of humour. Ice hockey incorporates all facets of life.

There are documented, published stories, and more unrecorded ones, some about players who originate from Northwestern Ontario. Several of the more interesting and less-known tales are the following:

- Tom Martin, who played for three different NHL teams, had his junior playing rights traded in 1983 by the Seattle Breakers to the Victoria Cougars of the Canadian Western Hockey League (WHL) in exchange for the Cougars’ used team bus and future considerations (!) (Diamond et al., 2000, p. 1384);

- In retirement, former NHL Detroit Red Wing, controversial Howie Young, drove the travel bus for a hockey farm team because he wanted to stay in the hockey culture;

- Viking, Alberta (population 1,085), the home of the six NHL Sutter brothers, most likely has the highest per capita production of professional hockey players of any place;

- A man from China began ice hockey in Hong Kong in the 1970s;

- The Canadian Embassy team in Hong Kong in the 1980s wore uniforms that were donated to them by the Calgary Wranglers junior team of the WHL; the Embassy team’s jersey crest was a Chinese junk superimposed on a Canadian flag and its schedule included playing games in Mongolia;

- Several hockey player trading cards contain misinformation, often because players have similar names, e.g., Bob “Houndog” Kelly, who played for the NHL Philadelphia and Washington teams, has a card which contains both his statistics and those of Bob “Battleship” Kelly , who played for St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Chicago;

- On one of the flights that crashed, killing all aboard, on September 11, 2001 (9/11 terrorism day) was a former NHL player; and

- Engraved on the NHL Stanley Cup are the names of several fathers and sons, e.g., Lee Fogolin, Sr. (Chicago) and Lee Fogolin, Jr. (Edmonton) and Bobby Hull (Chicago) and Brett Hull (Dallas); also, there is a mother and son – in 2001, when the Colorado Avalanche won the Cup, the Senior Director of Hockey Administration, Charlotte Grahame’s name was engraved; then, in 2004, Charlotte’s son, John, had his name engraved as a member of the champion Tampa Bay Lightning. The team that wins the Cup gets to have the names of management and players engraved on it.

These are just some of the stories. But probably the most amazing story of all is that of the Kenora Thistles of Northwestern Ontario winning the Stanley Cup in 1907, for the brief period of sixty-three days. The story is told in great detail in several places (e.g., Chliboyko, 2007; Danakas & Brignall, 2006; Lappage, 1988; Wong, 2006), but it is worth being told again to every generation. This article at hand does that, in brief, and with renewed perspectives in bringing together all that is known about what happened.

When most people learn that a hockey team from the small Northern town of Kenora (formerly Rat Portage), Ontario, once won the Stanley Cup, they react with amazement. This is, in particular, because of the international magnitude that the National Hockey League has attained since the first year of the championship for the Stanley Cup in 1893. Kenora is the smallest town ever to win the Cup. The town’s population in 1908 was a mere 6,257.

The Stanley Cup in 1893, the first year of the championship.

First, the Kenora Thistles’ story needs to be put in appropriate context:

The Birthplace of Ice Hockey

Though disputed, the birthplace of North American ice hockey is thought to be Windsor, Ontario, Canada where, around 1800, the boys of Canada’s first college, King’s College School (established in 1788), adapted the exciting field game of Hurley to the ice and it was called Ice Hurley. Over a period of decades, Ice Hurley gradually developed into Ice Hockey, with its growth-place being Nova Scotia, after soldiers at Fort Edward in Windsor took up the game and carried it with them when they were transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Following are excerpts from Danakas and Brignall (2006)’s excellent book that are pertinent to the flow of this article at hand:

The Stanley Cup in the Early Days

“Lord Stanley, Earl of Preston, was the Governor General of Canada. In 1892, he wrote a letter to the Ottawa Athletic Association. It stated that he wanted to create a new hockey championship. Each year hockey teams would compete to decide the best in the country. The winning team would take home a cup and keep it until the following year. Soon afterwards, Lord Stanley purchased a silver cup for 10 guineas (about fifty Canadian dollars). He set the basic rules of the competition, which was at first called the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup. (p. 25)

In the early 1900s, there was no single league throughout Canada. Instead, there were many leagues across the country. The senior leagues were the top level where the best teams played. Only senior teams could compete for the Stanley Cup. (p. 21)

The Stanley Cup used to be a challenge cup. Each season, the teams in the league of the Stanley Cup holder competed to decide the new champion. The champion of the league became the new cup holder. Champions from other leagues could then challenge for the cup. If the challengers won, they took the Stanley Cup home with them. (p. 31)”

Sometimes Stanley Cup holders faced as many as three challenges in a season. Challenge games were usually played on the home ice of the cup holders. The trustees, or caretakers, of the cup decided which teams would be allowed to challenge. They had the right to turn down a challenge. (p. 41)

The Stanley Cup started as a competition for amateur teams. Amateur athletes are not usually paid to play. Players who receive pay are called professional athletes. By 1909, both amateur and professional teams had won the Stanley Cup. Since 1910, only professional teams have played in the championship. (p. 70)

Teams and Games in the Earlier Days

Kenora and the Evolution of the Thistles 1907 Team

Kenora’s first name was Wagush-Onigum Kee-way-den. That’s what it was called by the Ojibwa, which was one of the largest native groups in Canada. Wagush-Onigum refers to the portage, or route, of the muskrat. Kee-way-den means “north.” Together, the words stand for “rat portage at the north end of the lake.” (p. 65)

Kenora, Ontario used to be called Rat Portage. The town is located at the north end of the Lake of the Woods. It is on the western edge of Ontario, close to Manitoba. … (p. 11)

At the turn of the twentieth century, Rat Portage (population around 3,000) was a trading post that grew haphazardly. When the train finally came through in the 1880s, it was a rough little town where many worked in the local lumber yards or fisheries or mined gold. The families were drawn to sport and playing ice hockey became a popular way for especially fathers and their sons to pass the cold winter months.

In 1894, the Kenora Thistles Hockey Club was founded under the name the Rat Portage Thistles, with Thistles referring to a Scottish flower. There was a men’s team that played at the intermediate level against other intermediate-level teams in the Manitoba leagues. As well, there was a junior Thistles team of boys between the ages of twelve and sixteen —many of them the same or younger brothers of players on the men’s team. The father of one of the boys, Billy McGimsie, owned the local rink (Wong, 2006, p. 181). The junior team, with their toughness, speed, skill, and hard work, became better than the intermediate Thistles’ team. At the beginning of the 1903 season, the Thistles were accepted into the senior league of the Manitoba and Northwest Hockey Association. In that year, they were champions of the Manitoba senior league, challenged Ottawa for the Stanley Cup, and lost. In 1905, the Western Canada Hockey League and the Manitoba and Northwest Hockey Association combined to form the Manitoba Hockey League. That year, the Thistles were league champions, and challenged the Ottawa Silver Seven for the Stanley Cup, travelled to Ottawa and handily won the first game. However, they lost the second game, reportedly because of Ottawa’s rough play, the soft ice “dirty work” of the Ottawa Arena Company, and the referee’s calls. Ottawa officials disagreed. In the third tie-breaking championship game, the Thistles lost to Ottawa 5 – 4. The play was dirty and the refereeing favoured Ottawa.

On May 11, 1905, Rat Portage was renamed Kenora. The “ke” and the “no” came from the names of the nearby towns of Keewatin and Norman. The “ra” came from Rat Portage. Its hockey team became The Kenora Thistles and it became Manitoba Hockey League’s champions in the 1905–1906 regular season. By March, 1906, the team had won the Stirling Cup as the best hockey team in Western Canada. It again issued a challenge for the Stanley Cup but there was a problem. The problem was that because the season had ended late, the early spring was turning the ice to mush out east. This ultimately delayed the Stanley Cup championship series until January 1907, and it was the Montreal Wanderers, the new champions of the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey League and also the new holders of the Stanley Cup, that the Kenora Thistles would be playing. Finally, dates in late January 1907 were chosen for the two-game series, to be played in the Montreal Arena.

The Months Leading Up to Kenora’s Winning the Cup

At this point, Canadian ice hockey was becoming increasingly serious, as was the Thistles desire to win the Stanley Cup. The Thistles were one of the last senior league hockey teams in Canada made up mostly of hometown players. Other teams tried to coax Thistles players away. Large sums of money were at stake. Kenora fans knew that eventually their top stars would leave for better paying deals somewhere else, e.g., in the East or the United States. The Eastern teams, such as the Montreal Wanderers, had already embraced the new attitude in professional hockey of just wanting the best talent and being willing to pay them alluring salaries.

Through a series of events, the Thistles seconded Art Ross from Brandon and two other “ringers”. [Ross was originally from Montreal and has an NHL trophy named after him.] The team travelled by train to arrive in Montreal a week before the series.

The Montreal Wanderers in 1907.

The Montreal home team lineup included Riley Hern in net, Hod Stuart at cover point, and Lester Patrick at rover. The Thistles won the first game 4 – 2. As was usual, the Kenora community followed the game through telegraph reports.

The second game was very rough physically. With less than five minutes remaining, the score was tied at 6 all. Some breaks in the refereeing then came to the Thistles and they won the game 8 – 6 to capture the Cup. [Of interest, the Kenora Thistles lay claim to introducing the tube skate into the game of ice hockey (Lappage, 2006, p. 93), and they were the first team to develop “combination plays” that gave them control of the puck for a large percentage of the game (Lappage, 2006, p. 93).]

The Kenora Thistles’ Stanley Cup championship

photograph. Back row: team president Lowry

Johnson, Russell Phillips, coach and trainer

J. A. Link, and team manager Red Hudson.

Middle row: Roxy Beaudro, Tom Hooper,

Tommy Phillips, Billy McGimsie, and Joe Hall.

Front row: Si Griffis, Eddie Giroux, and Art Ross.

For reasons explained earlier, the Thistles had won what was actually the previous year’s Stanley Cup. The Ottawa Silver Seven were eager to challenge them again in a Cup series. Further, the Thistles found that their fellow teams in Western Canada wanted a crack at them as new champions.

Then, in early March 1907, the Montreal Wanderers lived up to their traveller name and arrived on the doorstep of the Kenora Thistles. The Wanderers had defeated the Ottawa Silver Seven to win the Eastern Canada Hockey League championship. Now they wanted the trophy they had lost just two months earlier.

The Thistles agreed to a two-game series to be played in Winnipeg on March 23 and March 25, 1907. They lost the first game 7 – 2 and won the second 6 – 5. But the total score, when the two games were added together, was 12 to 8. Only two months after winning the Stanley Cup, the Kenora Thistles handed it right back to the Montreal Wanderers.

Hockey in Kenora Since the 1907 Stanley Cup

From the high of 1907, the Kenora Thistles championship team steadily crumbled, as the talented players were picked up by other teams and paid good salaries. By the end of the 1907-08 season, they had dropped out of the senior league, and were playing exhibition games against the likes of Port Arthur and Fort William, Ontario.

After the 1907 Stanley Cup win, many of the Thistles found themselves helping other teams in cities such as Ottawa, Montreal, and Vancouver to win the Stanley Cup. Si Griffis was the last of the original bunch of Thistles to retire from hockey in 1919.

After 1907-08, the Kenora Thistles’ red and white team went on to play in many international hockey championships, in places like Australia, Japan, and Europe. Kenora is still the smallest town to ever win a major sports’ championship and the Thistles are one of Canada’s oldest athletic clubs, existing for over 110 years.

Professional hockey players from Kenora over the years include Neil Strain, Henry Harris, Gary Bergman, Bob Bailey, Don Raleigh, Dennis Olson, Curtis Bowen, Rick St. Croix, Tim Coulis, and today’s NHL Los Angeles King, Mike Richards. Richards played for an atom league team named the Kenora Thistles (Chliboyko, 2007). Many more potential professional players currently play in the Kenora minor hockey system, some for a team in their appropriate division called the Kenora Thistles. Some players in that same system went on to play Junior, University or College hockey, or hockey overseas.

Conclusion

Imagine: it is the year 1907. You live in Kenora, Ontario, a tiny, tough community. Your hockey team, the Kenora Thistles, win the Stanley Cup as the best ice hockey team in North America — and, by imaginative extrapolation — the world, by beating the rich, big-city Montreal Wanderers team known for being a powerhouse.

Now Imagine: it is the year 2013. You live in Kenora, Ontario. The Kenora Thistles and Kenora, as a hockey town, are still of high profile. The living relatives of the players on the Thistles 1907 Stanley Cup championship team (all of whom have passed away) may know nothing or a lot about what happened. No matter, the championship is still talked about.

This story will always have a happy ending. It reveals the true essence of ice hockey— its competitiveness, its passion, its appeal to all ages, and the great lengths to which players go to be winners, “dirty tricks” and all. The players on the 1907 Kenora Thistles team were romanticized as the epitome of what hockey players should be — fast, skillful, dedicated, loyal, and well-behaved. The majority of them was comprised of hometown boys. Five Kenora Thistles have been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, Ontario: Art Ross, Si Griffis, Billy McGimsie, Tom Hooper, and their former captain, Tommy Phillips.

Ice Hockey has changed in that the professional players and the Stanley Cup are now known internationally. Further, justifiably, there is now an upscaled concern about the safety of players, particularly with respect to concussions. However, hockey has not changed as to its representing the true grit that the scrappy bunch of 1907 Kenora Thistles possessed.

Despite all of the politics and adversity, the Thistles triumphed , and left their mark upon the early development of hockey in Canada. Was it really how the accounts of how things happened say it was? Or was it another way? With all of the players deceased, it can never be known. Whatever, out of the mists of the past, comes the ever-captivating story that is the subject of this article at hand. Long live the 1907 Kenora Thistles Stanley Cup story!

Professor Doug Thom

Postscript

The author’s son, Wes Thom, played for the Kenora Thistles senior AAA team (1907 Stanley Cup champions) during the 2011-2012 season.

Works Consulted

Carrier, R. (1985). The hockey sweater. Toronto: Tundra Books.

Chliboyko, J. (2007, April–May). When rats ruled the rink: The small-town Rat Portage Thistles battle doctored ice and big-city attitude to become Stanley Cup champs, though their victory proved fleeting. The Beaver, 16–21.

Danakas, J., & Brignall, R. (2006). Small town glory: The story of the Kenora Thistles remarkable quest for the Stanley Cup. Toronto: James Lorimer.

Diamond, D., Duplacey, J., Dinger, R., Fitzsimmons, E., Kuperman, I., & Sweig, E. (2000). Total hockey (2nd ed.). Kingston, NY: Total Sports.

The Kenora Library. Various copies of the Rat Portage Miner and Kenora Miner newspapers, 1895 on.

Lappage, R. (1988, December). The Kenora Thistles Stanley Cup trail. Canadian Journal of History of Sport and Physical Education, 10 (2), 79–100.

Mills, B.D. “Out of the Mists of the Past.” A website dedicated to the Kenora Thistles.

Thom, D.J. (1978). The hockey bibliography: Ice hockey worldwide. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Recreation.

Thom, D.J. (1981). The total hockey player: Brawn is not enough. Calgary: Detselig.

Thom, D.J. (1986, February). The arrival of the total hockey player. Orbit 77, 17(1), 21–23.

Thom, D.J. (1988, April). The superior hockey player. Orbit 86, 19(2), 18–19.

Wong, J. (2006, summer). From Rat Portage to Kenora: The death of a (big-time) hockey dream. Journal of Sport History, 33 (2), 175–191.

U18 Kings Bow Out at West Regional – Schultz, Regina Dominate the Ice

U18 Kings Bow Out at West Regional – Schultz, Regina Dominate the Ice