FORT WILLIAM FIRST NATION, ON – The ability to share whole knowledge with each other is the ability to come to understand each other. With one day left to comment to the Ministry of Ontario about the protection of the Loch Lomond Watershed and Thunderbird Mountain Area (Nor’ Wester Mountains) Kevin Porter shares his knowledge of the land.

Traditional Customs part of FWFN Future

Sharing circles are an important principle custom of many Anishinabek (Ojibwe),

peoples. The circle is meant to suggest “inclusiveness and the lack of hierarchy” and represent “interconnectedness, equality, and continuity.” All circle participants share their views of a subject. The person speaking holds an item like a feather to address the subject and must be respected and listened.

Traditionally the shape of the sharing circle reflected “the seasonal pattern of life and renewal and the movement of animals and people were continuous, like a circle, which has no beginning and no end”.

The earth, sun, moon, seasons and movement of the earth all happens in a circle. Many Anishinabek (Ojibwe), people’s cultural items like the drum, wig wams, sweat lodges, dream catchers and medicines wheel are all made in a circle.

Sharing Knowledge “Beautiful” Song Video

Kevin Porter an Ojibwa, customary youth from both Fort William and Garden River Ojibway First Nation and a nominee for the 2013 Aboriginal Peoples Choice Awards for his debut album Singwauk; drove to Fort William First Nations from Garden River First Nations to help in the protection of the Loch Lomond Watershed for future generations.

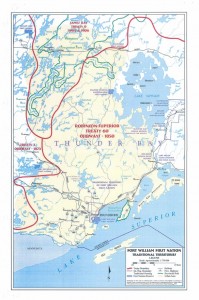

In 1850, Fort William First Nations signed the 1850 Robinson Superior Treaty. After 1850 the membership territory included large parcels of land from Pie Island to Kakabeka Falls. Through expropriation the reserve lost over 8, 630 acres of land since the 1800’s.

All land is Anishinabek territory but on Canadian government record Fort William First Nation has become a small land owner. The small parcel of land the reserve has left is land locked by the Nor’ Wester Mountains, Lake Superior, Kaministiquia River and the municipalities of Neebing and Thunder Bay. Much of the land left is swamp or industrialized land at the base of Mt. McKay.

The last parcel of land to continue practicing spiritual and cultural practices like hunting, fishing, sacred ceremonies, traditional food and medicine gathering is in the Loch Lomond Watershed. Some people of the community would like to protect the watershed for future generations to have access to pristine drinking water and areas to practice traditional customs.

The Loch Lomond Watershed is set to have an industrial wind farm built slightly on and near traditional territory. Fort William First Nation, City of Thunder Bay and others share in the ownership of the Nor’ Wester Mountains (Thunderbird Mountain) and Loch Lomond Watershed. The City of Thunder Bay wants to develop an industrial wind farm on their parcel of land between the governments Area of Natural Scientific Interest and the First Nations Loch Lomond Watershed.

In keeping with his tradition, Kevin wants to see the Loch Lomond Watershed continue to sustain and feed the spirit and physical body of the Anishinabek people and all inhabitants in the circle of life for future generations.

He participated in a Save the Nor’ Wester rally while visiting the area and shared with many people his knowledge of the local Anishinabek and his relationship to Anemki (Thunderbird Mountain) also known as the Nor’ Wester Mountain Range.

Porter an eagle clan member is a traditional singer and drummer shares his view of an industrial wind farm going partially on and near the Fort William First Nation traditional territory.

He speaks about the cultural history of Thunderbird Mountain and the need to share it, that water is a life giving source, the importance of protecting the land, traditional foods, medicine and waters of the Loch Lomond Watershed for current and future use and how Anishinabek can continue to participate and learn to be whole with themselves and their culture by connecting and reconnecting with the ‘Thunderbird Mountain’ and the Loch Lomond Watershed.

“The sacred place of Thunderbird is where the Thunderbirds gather, it’s a sacred place”.

“The reason I want Thunder Mountain to remain intact is to help educate our people and the world about the history of the area and the importance of it and to keep the water because it is a life giving source and the rest of the world needs to understand how important that water source is to our nation and all nations as time goes on and as time progresses, those waters need to be kept to turn back to”.

In 1993, George Pine introduced him to the pow wow trail. The introduction of culture stuck with Kevin and he began to sing, drum and to continue learning his culture. Kevin has sang with Chargin’ Horse, Crazy Spirit and Thunder Mountain. His love for his culture, people and home land is evident.

“The beauty of the area should be seen, the creator has given us, not just our people but everyone to come to and to see the people and the land and to remember the history”.

Kevin states the reason to protect the land, “Is so that our people have the ability, the choice to get to know themselves and that source of water is our life giver and if we take that water and poison or damage it, the future generations won’t have water to drink and they would have to find more technical ways to”.

He wants the lands protected for people to get to know themselves to understand the true importance of this land and why his people have been protecting and praying for the land for many years.

“We need places to hunt and eat those natural things that come from the land and to preserve those because that’s what creator gave us to eat and those are the healthiest for our bodies. For our people pork and potatoes are poisonous and doesn’t belong in our diet and we understand its poisonous to our diet and those are the reasons the people protect our land. So that the people can eat properly and to be healthy.”

Kevin Porter words build the capacity for land stewardship and the need for proper sustainable land planning and continue practicing and sharing cultural knowledge.

He shares an important song called “Beautiful” from his debut album Singwauk.

In sharing our knowledge with each other we can come to a better understanding of our neighbours and their history, needs and sovereign rights and traditional governance like the members of Fort William First Nation and all the signatory’s of the 1850 Robinson treaty.

Kevin Porter’s insightful knowledge about Thunderbird Mountain, tradition and protecting land and water allows one to understand his and other Anishinabek peoples relationship and view of Thunderbird Mountain and the need to protect it for current and future generations to connect with the language, land, culture, water, food and traditions of it.

Thunder Mountain History

“Mt. McKay and Nor’ Wester Mountains was originally known as the “Thunder Mountain” (Animikii-wajiw in the Ojibwe language and locally written as “Anemki-waucheu”). The mountain is used by the Ojibwe for sacred ceremonies. Only with the construction of the road were non-First Nations allowed on this land.”

There are many legends about Thunderbirds in the Ojibwe and other cultures. “The Thunderbird is the symbol of the Ojibwe people.” In the physical world the Thunderbird is the most significant supernatural creature , than humans and other inhabitants and then water lynx and snake. “The Thunderbird is thought to create wind by flapping its wings and thunder and lighting by opening and closing its eyes.” Some Ojibwe cultures have Thunderbird practices performed at Sundance ceremonies where the Thunderbird nest is danced to and a pipe and medicine is prepared. Thunderbird Mountain of Fort William First Nation is a sacred place with many stories like this to be shared. Our knowledge is in the land and if people can’t connect to the land its hard to pass on the knowledge.

Get Involved:

Today is the last day to submit comments to the Ministry of Ontario by midnight. But all Anishinabek and non-Anishinabek people are encouraged to continue writing to the government (Send submissions to: Submit online comments to www.ebr.gov.on.ca/ (project number 011-8937)

Fort William First Nation Industrial Development in the Loch Lomond Watershed:

In the case of Fort William First Nation and a much disputed and controversy potential wind farm development on the Nor’ Wester Mountains (Thunderbird Mountain Area) and the Loch Lomond Watershed it has led to the question of consultation between a developer and Fort William First Nations, 1850 Nation to Nations signatory’s, Métis and other First Nation groups who may be affected by any development on the Nor’ Wester Mountains (Thunderbird Mountain Area) in and near the Loch Lomond watershed and traditional territory.

Fort William First Nation membership asserts they were not consulted about this project based on the following consultation practices:

FWFN owned the Loch Lomond Watershed and it was expropriated by the City of Thunder Bay to use as a watershed, and they should have been consulted on any potential developments in the area, on and near traditional land according to news reports and people.

Bill 150, Green Energy and Green Economy Act was introduced in the Ontario legislature February 23, 2009. It is unclear if their was a public consultation with First Nations governments and peoples in the creation of the act and consultation process. However, in the act, one aboriginal law example in the Green Energy Act under Part I Interpretation and General Application Definitions and interpretation states;

Interpretation

(2) This Act shall be interpreted in a manner that is consistent with Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and with the duty to consult aboriginal peoples.

The Green Energy Act affects many other acts from the Clean Water Act to the Public, Conservation and Environment Acts. Under federal aboriginal laws people feel the First Nation Clean Drinking Water Act, Fisheries Act and Migratory Birds Convention Act needs to be incorporated in any development on traditional and reserve lands.

The Ontario Government also devised REA Aboriginal Consultation Guide and identifies the need to contact all First Nations people affected by a project and have continuous consultation with band members and council in accordance with the bands traditions and needs.

The Government of Canada strongly advises authorities conducting things like environmental assessments to include traditional land and cultural knowledge of First Nations Peoples. (Source: Click here)

“Many developers contact communities like FWFN to have general meetings with band councillors and administrations to hear business ideas. Under Federal legal duty to consult many people feel it is the legal duty to appropriately notify and engage in meaningful consultation with the entire band membership and council about projects, that will affect reserve and traditional lands. All non-band members engaging in potential business affairs with First Nations peoples are possibly Federally legally bound to aboriginal rights and the duty to consult.”

“Too some; due to the collective nature of First Nations rights and societies, authority to govern is thought of as emerging from the community as a whole. There is no division of powers between a Band’s collective membership and its Chief and Council. A Band Council and Band membership hold collective rights, and therefore certain decisions must be made by a vote of the membership, such as the designation of a parcel of reserve or traditional land to be developed by a non-band member or corporation. Projects like an industrial development on traditional land and near the watershed must have the approval of the entire band’s membership.”

According to many people it will be Fort William First Nation’s sovereign rights with the arrangements of Federal reserve and traditional lands governance and forms of land tenure set out by the binding legal rights under the living agreement of 1850 Robinson Superior Treaty, the Constitution Act and under the Federal laws to protect the Loch Lomond Watershed for current and future generations.

If this project will negatively impact traditional lands from blasting and clear cutting on the mountain to install turbines and sovereign treaty, food and water rights than people like Kevin Porter has a cultural duty to protect this land and assert sovereign rights from devastation and traditional impacts.

Band councillor Wyatt Bannon said in a radio interview in June of 2013 the community would like to see the company appropriately site the project to minimize impacts to the land, developer and communities and for future generations to be able to inherit the land in an intact and healthy manner for future generations.

Perhaps if all involved had participated in a sharing circle known as modern consultation and included the knowledge of the youth like Kevin Porter; all involved may have learned in the sharing of knowledge, the Loch Lomond Watershed and Thunderbird Mountain continue to be a sacred, important and spiritual place many want to protect for current and future generations. Perhaps we all have a thing or two to learn about traditional governance.

The MOE under the director’s title 47.5 has duty to consult with aboriginal peoples and justify the approval of this project.

If you would like to protect the Thunderbird Mountain (Nor’ Wester Mountains) and the Loch Lomond Watershed share your knowledge and comments with the Ministry of Ontario by midnight tonight and continue sending your letters. It’s never too late!